A Painter's Secret Superpower

Unlocking the Palette with the Pigment List

A painter's secret superpower

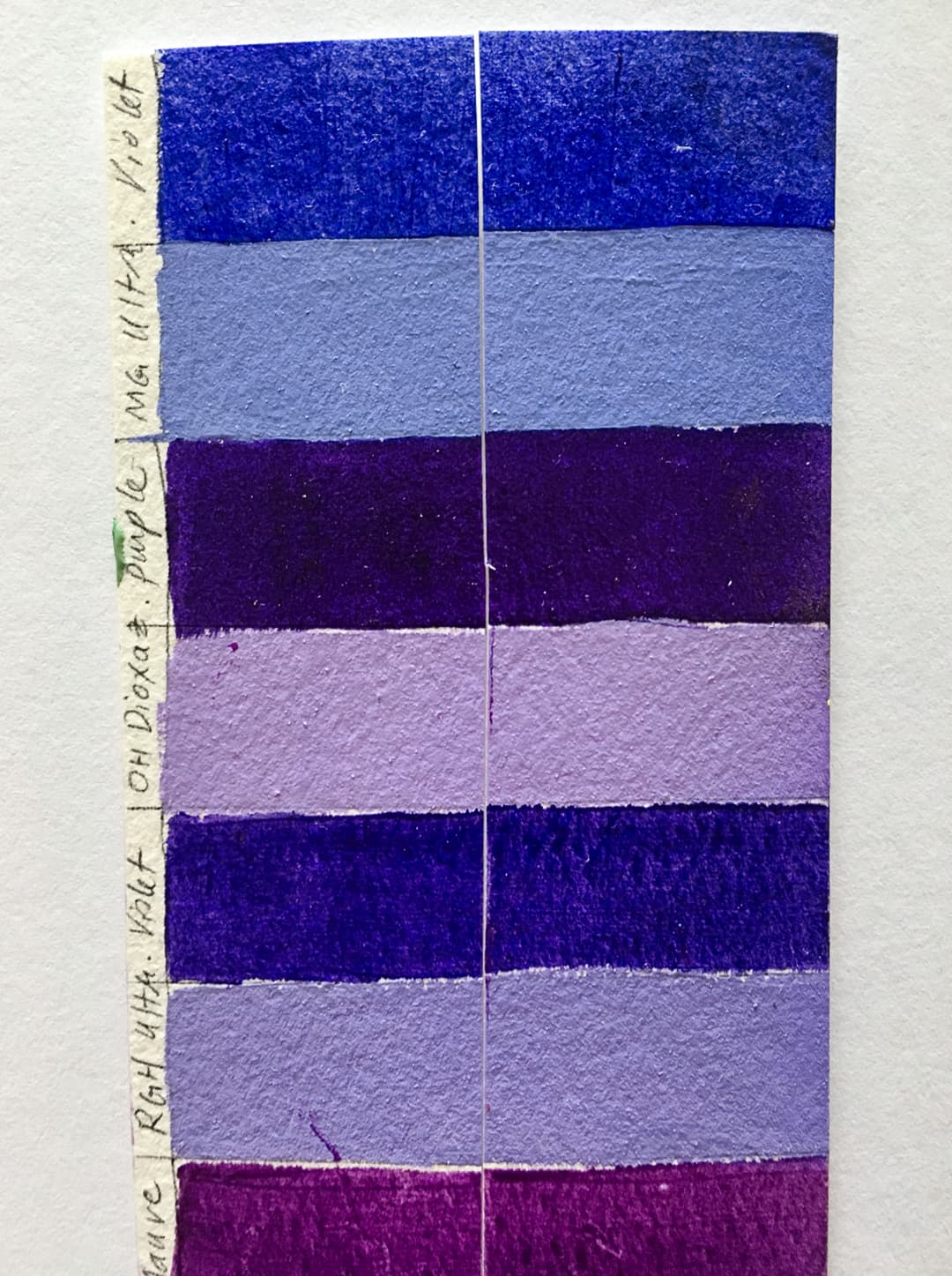

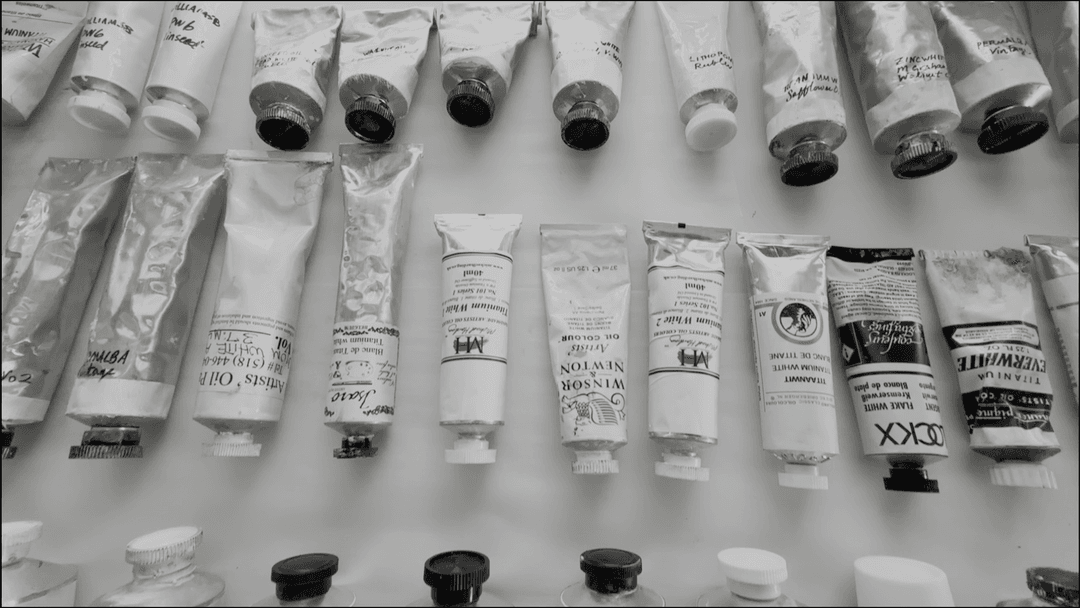

Featured Paints

A Quick List of Artist Pigment Codes

Below is a list of the main pigments that are used in artist paints along with a little bit of information about each one. To find out more about a pigment, you can look it up in the Pigment Notebook.

Here we take a quick look at the rainbow of artists' paints and the pigments that give them their fabulous color. Rich reds, off-the-charts-oranges, luminous yellows, verdant greens, cool blues, and mysterious violets along with pale ivory, intense black, rich brown, and ice white. Understanding pigments are one of the things that can elevate your painting more than almost anything-- from color mixing to studio safety, this knowledge is crucial. However there is so much to know that this is an incomplete source, more like a directory to give you a jumping-off point for your own explorations.

Understanding pigments can help you to gauge a color's

-Lightfastness -Toxicity -Color Mixing Behaviors

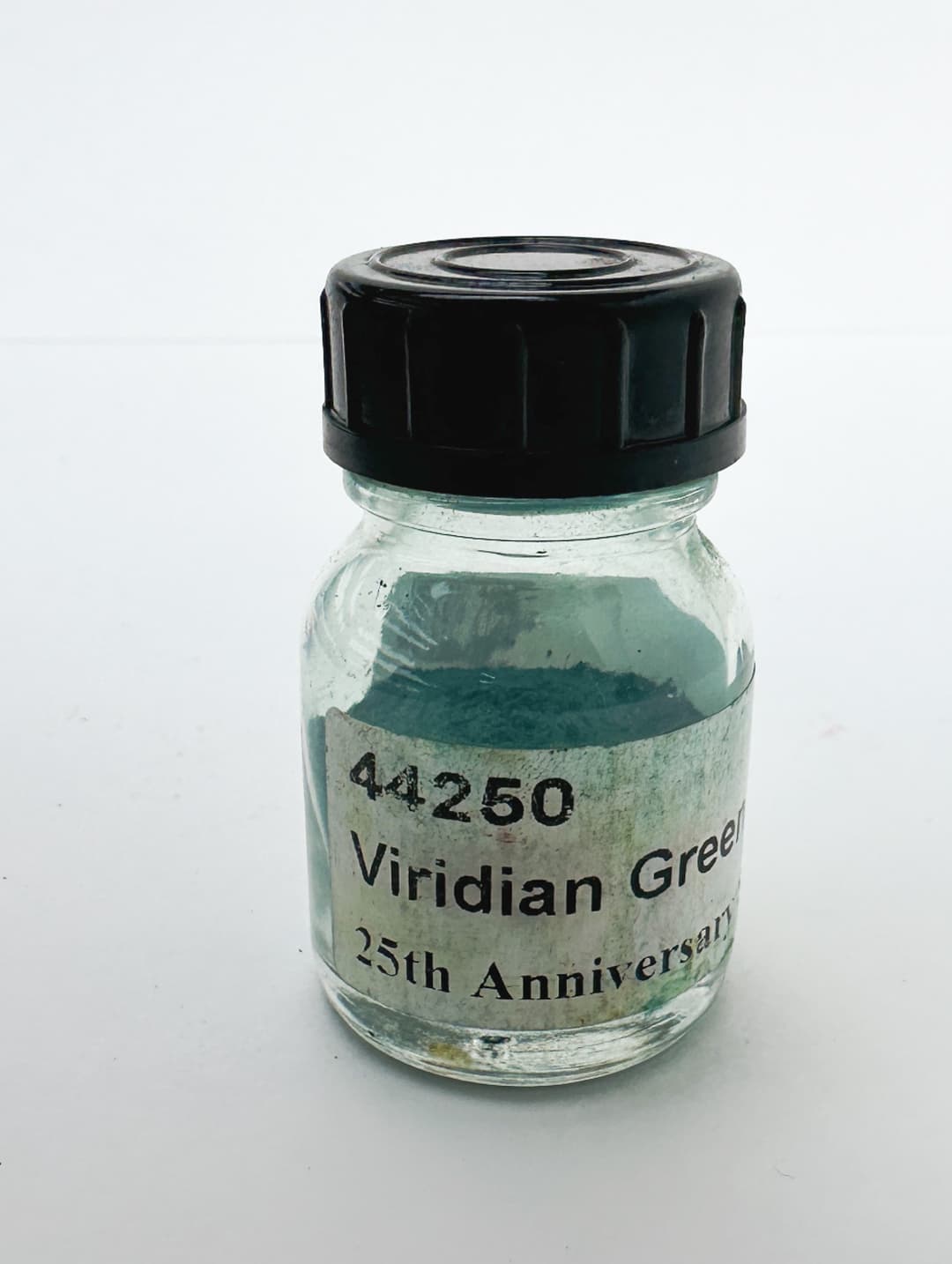

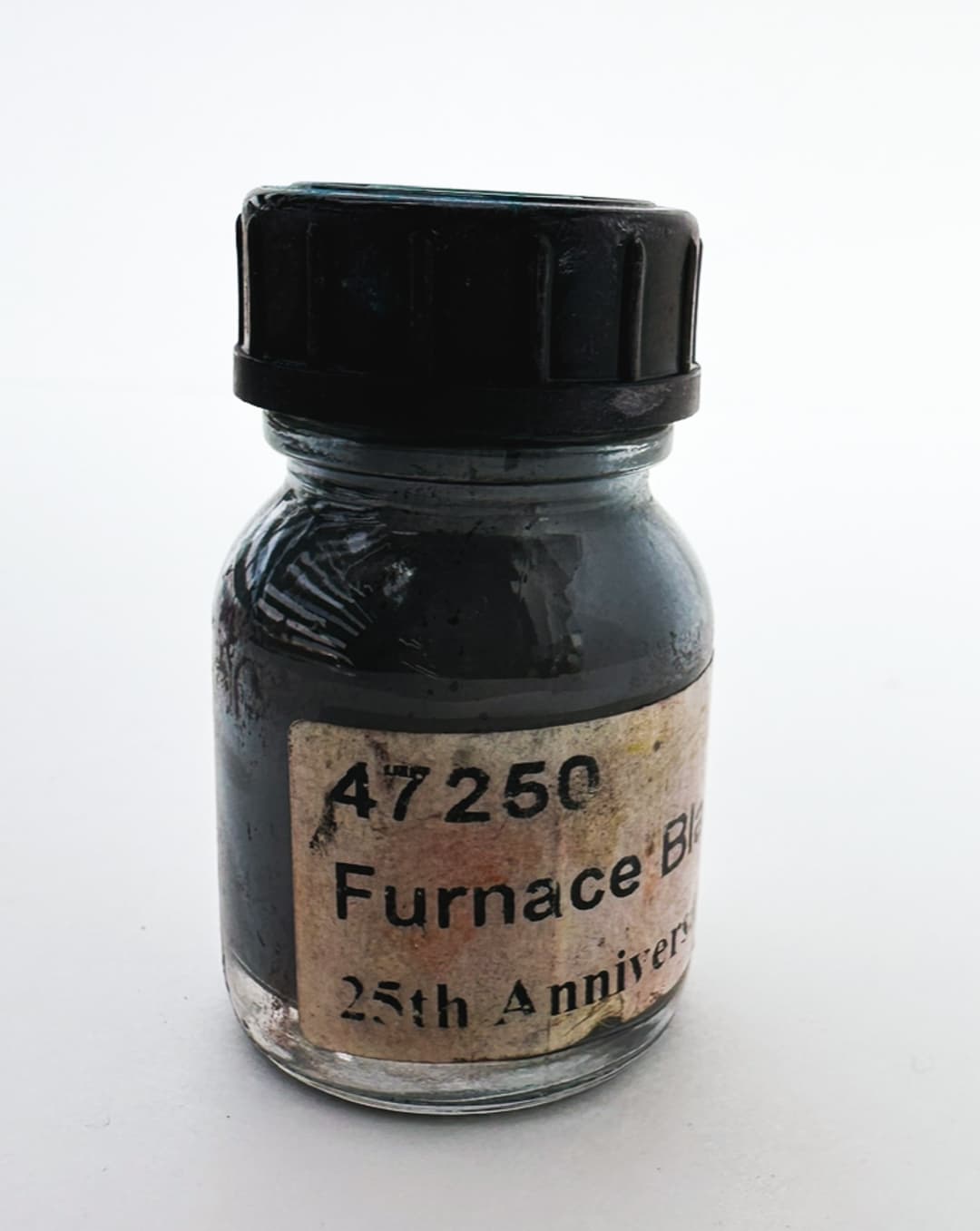

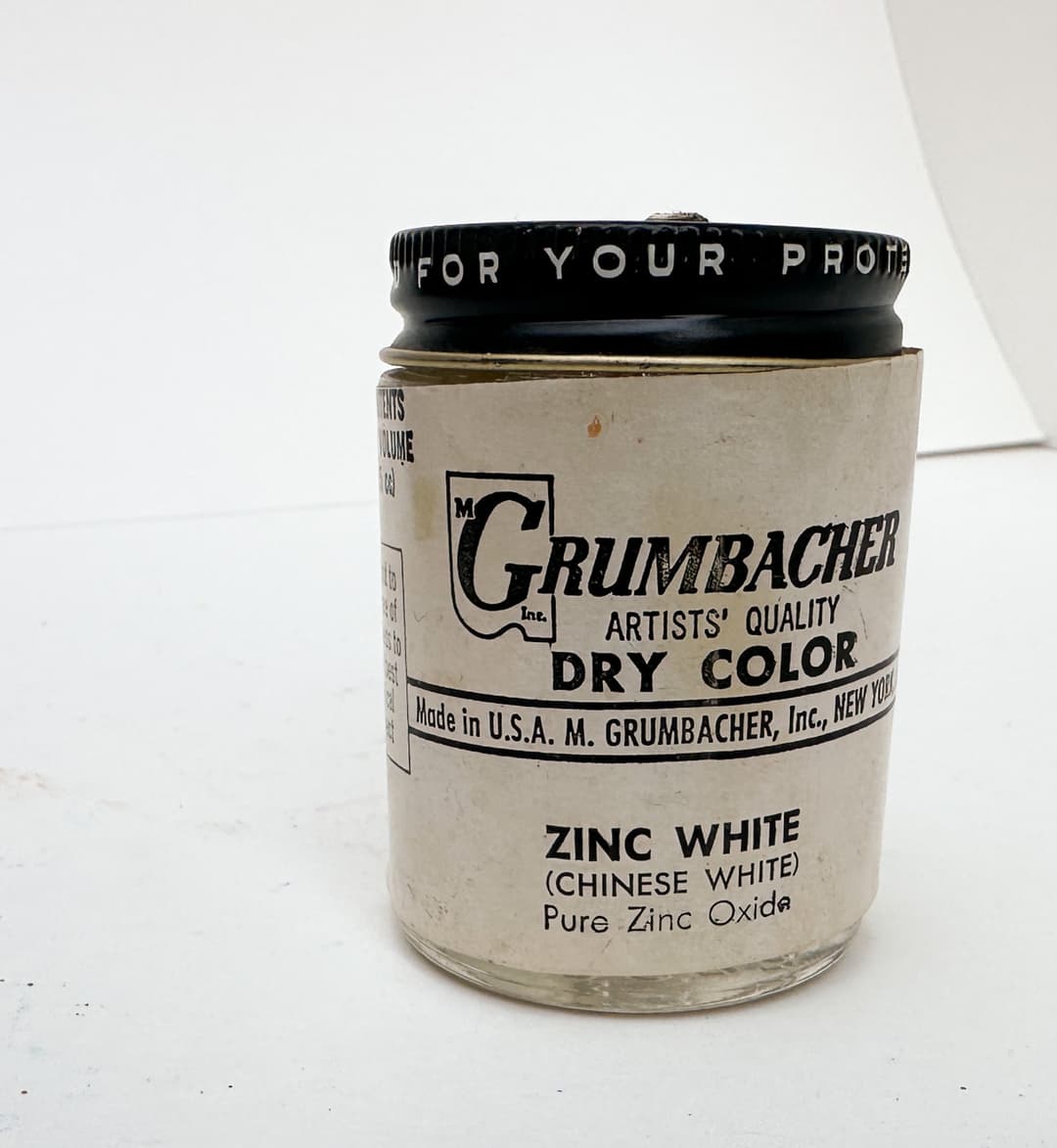

Antique pigments, A.H. Abbott & Tyl

But first! What is a pigment?

Paint is made of pigment and binders

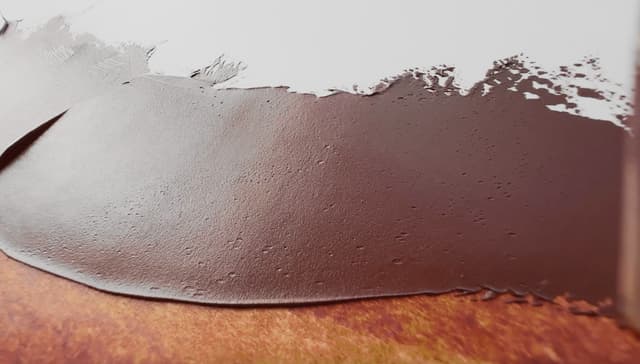

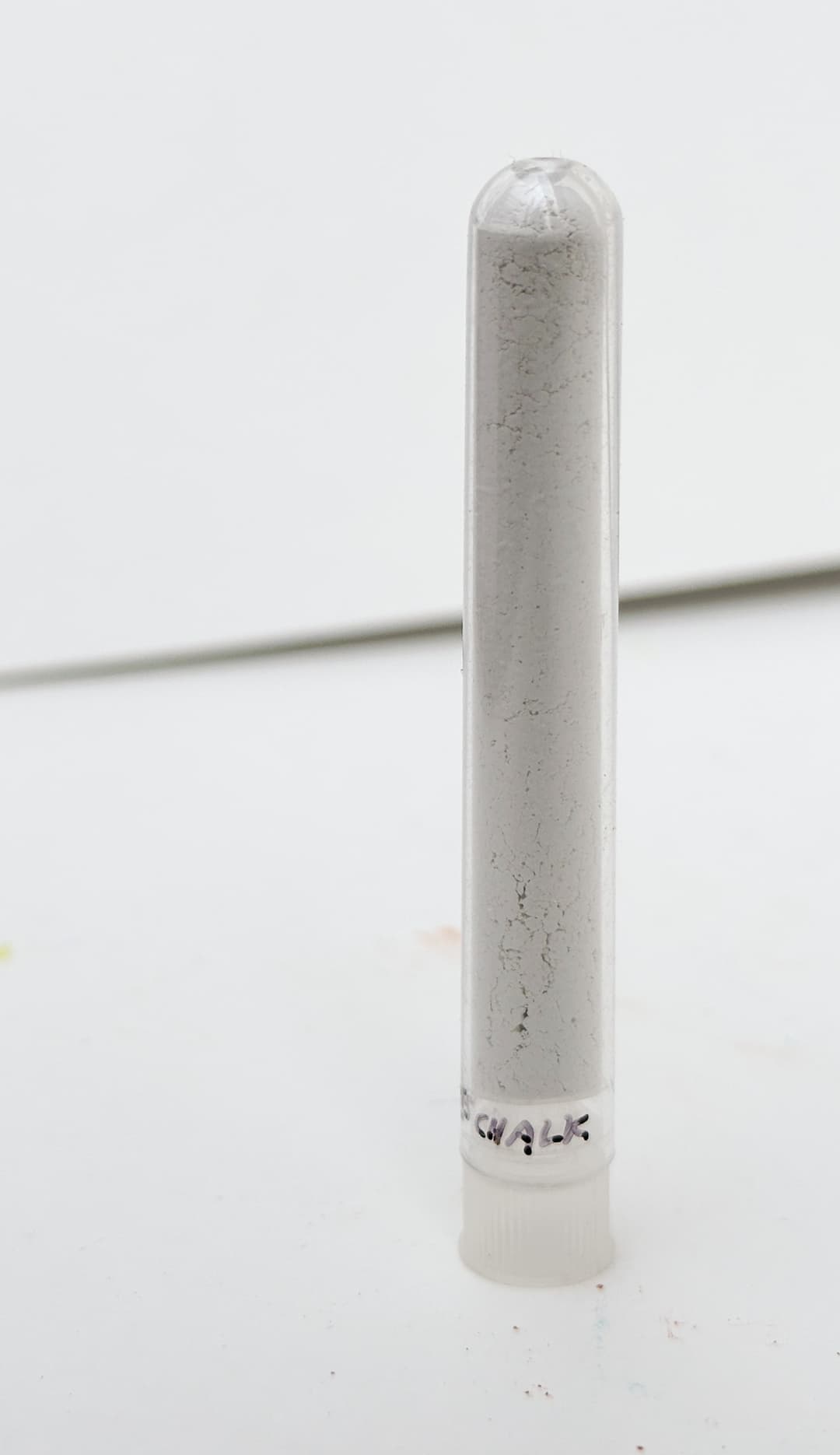

In short, pigment or dyes give paint its color. In simplest terms, think of colored powder which is combined with a clear binder to make paint. Colloquially we tend to call all of the colorants pigments, but there are some fine points of distinction here. There are lots of resources online that delve into the various categorizations of pigments, so we will not go into the categories of pigments here. Below you'll find a list of pigments in artist paints with a few words about each.

However, we do get some questions about what pigments are not. Pigment codes are not -RGB or hexidecimal codes (those are used by graphic designers) -Pantone Colors -LAB colors

The above are systems that describe colors, while pigments describe materials. Some pigments are minerals or semi-precious gems, some pigments are dyes (for instance derived from roots), and some are synthetic chemical concoctions that you might encounter in printing inks or in a chemistry lab.

In other words, in some cases a spot color (think RGB, Pantone, LAB, whatever you might use to describe a spot color with a spectrophotometer) could be made with various mixtures of several different pigments. Concerns like lightfastness or toxicity may inform which pigments are used for a given application.

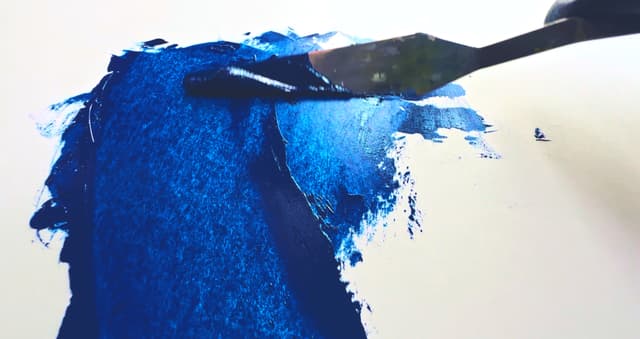

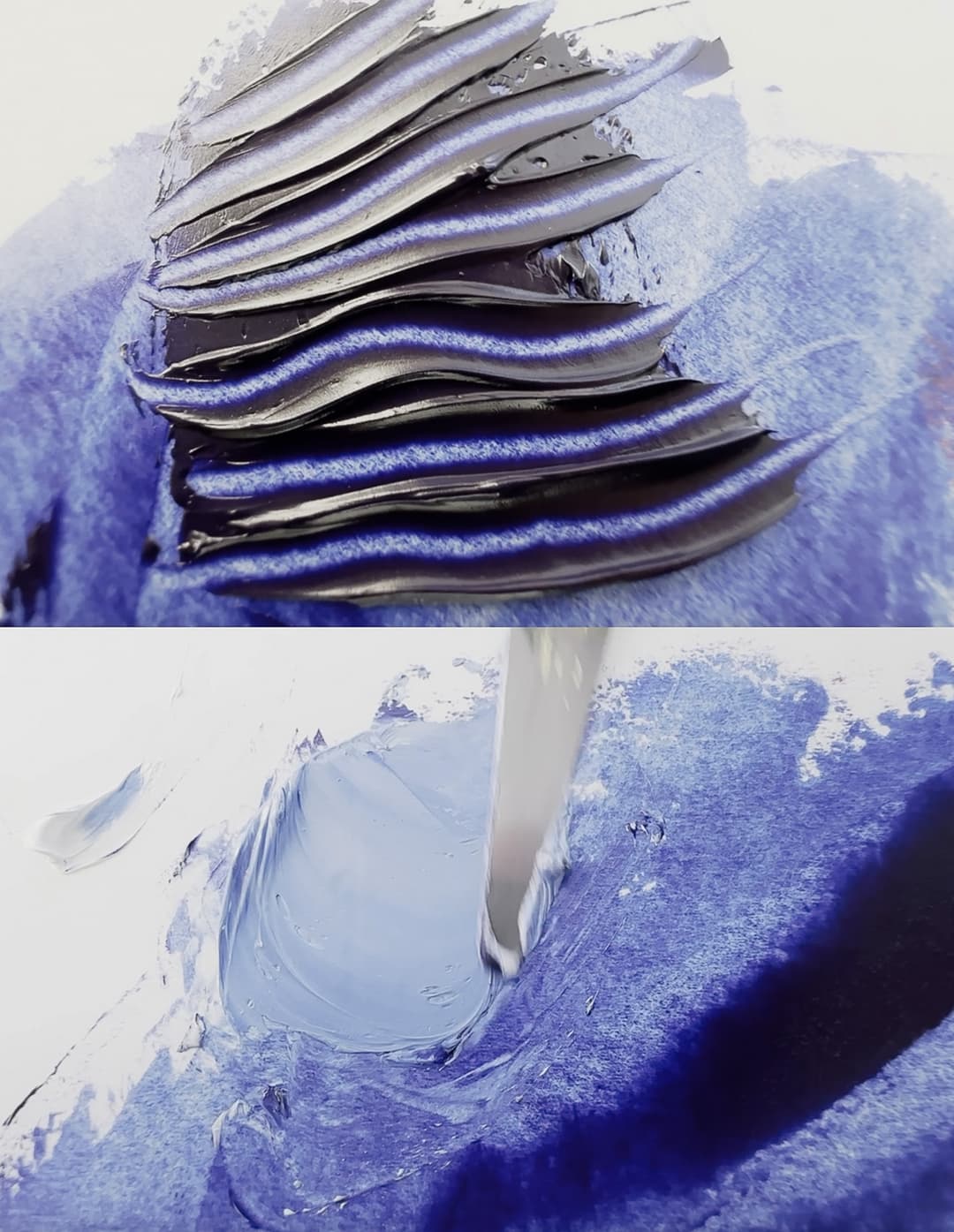

Paint in its simplest form is pigment and binder

How to Find a Pigment Code on a Paint Tube

All reputable paints will list the pigment codes for the materials they use

Every one of the tubes of paint in your paint box should have a pigment code on the back.

Paints that are a blend of colors should list every pigment in the blend. It is a major red flag when a brand does not list their pigment codes.

Here's a quick primer on how to decode them. The "P" stands for pigment, followed by a letter that stands for the main color grouping. So we have

PR = red, PO= orange, PY= yellow, PG= green, PB= blue, PV= violet, PBr= brown, PBk or PBlk= black, and PW= white

and this is followed by a number. The numbers are just indicative of the order in which the pigment was added to the Colour Index, which is made by the Society of Dyers and Colourists. There is also something called the C.I. number, which can give a little bit more information about a colorant but these are not usually published on paint tubes.

Sometimes a person will encounter the same pattern where the letter N is used instead of P. This is another convention where natural dyes and other materials are sometimes listed as Natural Red, or NR, Natural Orange, as NO, etc. This custom follows the same pattern as the pigments but with an N for natural instead of a P for pigment, so the code reads NR, NO, NY, NG, NB, NV, NBr, NBk (or NBlk), and NW.

The pigment code on the back of a paint tube is one of the most important pieces of information on the tube. It's so important that we made the Pigment Notebook to make it easy to look up these codes and learn about the pigments in your paint. However it is rarer to find these codes in modern paints as the colorants tend to be less lightfast.

All reputable paint brands have a code that indicates which pigment is used to make a given color

Supplement this with your own research

Pigments are serious business

Far more could be said about every one of these pigments, so we recommend supplementing this resource with your own research as there is much more to discuss about each pigment than we go into here. Pigments are serious business and we make no warranties nor guarantees on the completeness or accuracy or even up-to-dateness of this continually evolving field of information-- you're responsible for doing your own research and also for developing your own best practices in the studio. Two resources we have enjoyed are artiscreation.com, written by David Myers, and a guide to watercolor pigments from Bruce MacEvoy, which will also apply to many oil and acrylic paints, though lightfastness can vary based on media. Though no one site has everything there is to know about pigments, these provide a good beginning point. There you can find more information on toxicity, Blue Wool Scale tests, and chemical composition. Also our understanding of lightfastness in oils is evolving, and the interactions of pigments in the same mix may have a greater effect than was ever previously realized.

In terms of health and safety, this is a complex and rapidly developing field which goes beyond our expertise. As we always remind readers, we are artists, and so we recommend seeking expertise from the toxicology experts. Monona Rossol, an art materials specialist and chemist who teaches at the University of Delaware has written several books. The 2001 edition of her book, The Artist's Guide to Health and Safety is one resource, but we encourage artists to seek up-to-date information which can be obtained by contacting her through her site. We also recommend consulting MSDS sheets as well as supplementing this with additional third party independent research on health and safety because that stuff really matters.

Quite a few artist pigments have never been directly studied for toxicity, so the absence of a safety warning does not mean a pigment is automatically safe. Many important artist pigments are toxic. Some hazards (lead, cadmium, cobalt, chrome, etc.) are well-known while others seem to lag in artists' awareness. We have been surprised to hear new research on several organic dyes and pigments which we were recently informed are likely to be carcinogenic, when previously no threat had been studied, so we treat all pigments with greatest care, according to best practices.

We made this quick look up so that you can find a pigment code quickly -- just type command+F or Ctrl+F to jump to a particular pigment.

We've compiled a list of many pigments used in artist paints in this brief listing. This is a very abbreviated key to help decode the most powerful piece of information on a paint tube- the pigment code. For those who are not as familiar with the pigment code, it's the little marking on the back of the paint that says something like "PY35." From that you can identify the pigment, and from there begin to research the lightfastness, sometimes the hue, the chemical properties of the pigment, and a whole lot more.

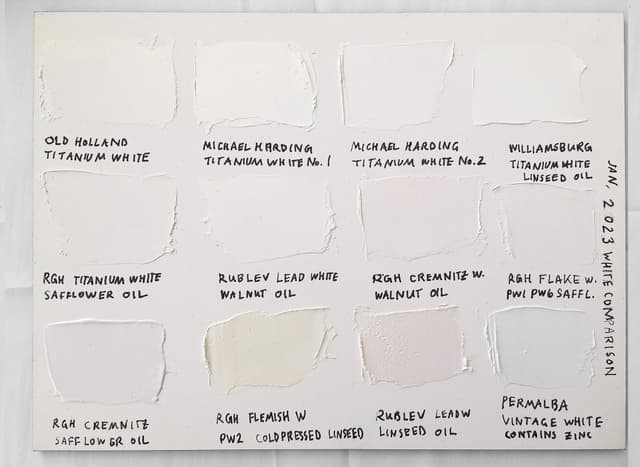

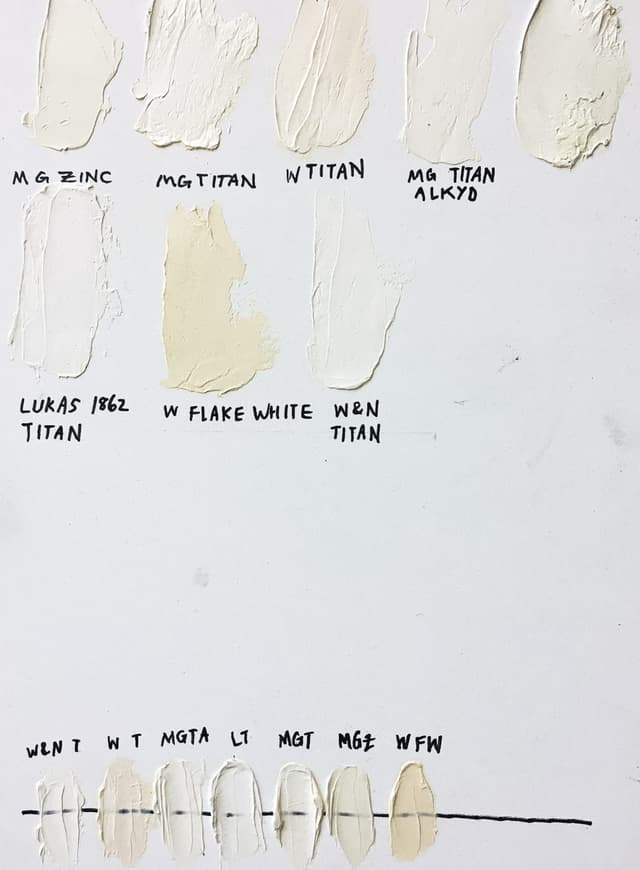

Please note that binding oils as well as the collection of additives, stabilizers, or extenders used in a paint may affect lightfastness in ways not discussed here. Specifically the choice of mixing whites has a surprising effect on certain pigments in oil painting. See Golden's research for more.

We have slightly higher requirements for lightfastness than some painters do. Ideally we do not like to see any falloff of lightfastness in tints (all 8's on the blue wool scale is ideal), as most of an oil painting is mixed with white unless one is using glazing techniques. So, when we say lightfastness is moderate, this refers to around a 6 on the blue wool scale, or even worse a 5. For some that is still acceptable, but we have fairly stringent requirements.

Please note: this guide does not discuss health and safety. Many important artist pigments are toxic. More detailed information on safety can be found in the manufacturer's MSDS sheets, and we always recommend supplementing these with additional third party research.

Red Pigments

The red group of pigments spans the deep, cool crimsons to near oranges. From deep cherry, to Ferrari, to tomato, we're always looking for the ability to hold color in sunlight when it comes to the red section. There are historical notes from Rose Madder, 20th century staples like the cadmiums, and even a few unusual ones like Potter's Pink.

Lightfastness is important in any pigment, however, reds are an area where we are especially attuned to look for paints that won't fade in tints. Many gorgeous reds do not hold up well enough over time to be considered for artist's paints. There are a few beautiful ones that artists love so much they are willing to bargain on the lightfastness, come what may.

There are several which, in our opinion shouldn't be made into artists' paint. Just by happenstance, these paints start our foray into red pigments currently in use by paintmakers.

PR3 - Toluidine Red. The first numerical pigment to be considered starts off a whole section of inadequate pigments. This abominable color has a blue wool scale of 3/8 (about ASTM IV category). If you are new to this, the way it works is higher the blue wool scale on a scale of 1-8 the better- eight is the best. For us, sevens mean moderate. Sixes are lower than we would use. A three for lightfastness is quite low.

Monona Rossol also writes that it may be a carcinogen as well as about potential serious health issues that could arise, so please consult her writing if you choose to use it.

PR5 - Naphthol Red DK. (One of several Napthol reds). Moderate to inadequate lightfastness. We were surprised to see this color found in a currently available Cadmium Red Imitation hue by a major art supplier, and they listed good lightfastness. Perhaps they found a better source for the pigment, but it might be worth doing one's own lightfastness tests.

This is another case where Monona Rossol's work about potential serious health issues that could arise, such as methemoglobinemia, so please consult her writing on pigments.

An array of red pigments covering the gamut from magenta to red-orange

Red Lakes and Historical Crimsons

Hard to know what's meant by these terms

Precise identification eludes the casual reader of National Gallery Bulletins and this interests us very much. NR3 and NR4 are both historical pigments made of insects, but the term Red Lake could refer to a variety of precise pigments.

This interesting and somewhat diverse class of terms have a way of leaving one wanting more in terms of clarity when reconstructing the palettes of famous painters. The names of the red lakes or red lac as it is sometimes called, display a specificity (like cochineal). Yet the terms can seem to rearrange and melt into one another again (is cochineal the same as kermes?) in one's peripheral vision.

Here we refer to the laked pigments of madder (also see notes on NR9), cochineal (NR4) - that much-discussed insect, and kermes, another often-mentioned insect and its associated dye (NR3)- which also has a way of blending into the cohcineal-natural-crimson-lake-listings in conservation history. Specifically, the term Red Lake could refer to reds made from Madder, the plant Rubia tinctorum L., Conchineal insects, Dactylopius coccus, and Kermes insects, Kermes vermilio. However the list does not stop there.

Some of these historical lakes have held up surprisingly well but many have faded (the Mona Lisa used to have red sleeves) and Van Gogh's purples made with eosin- another vibrant red lake- have turned from violet to blue. So while interesting research may be done on their composition and manufacture, as well as inquiry into why some red lakes have not faded so badly, historical red lakes on the whole are not considered lightfast.

On another note, were shocked to hear that there is a possibility that cochineal (NR4) may actually be a carcinogen along with other anthraquinones and that more testing is needed. While the dye produced from cochineal insects has not specifically been evaluated for this, it is similar to other anthraquinones that have been found to be carcinogenic. Other natural reds-natural alizarins or rose madders made from madder or chayroot (including NR6, NR8, NR9, NR10, NR11, and NR12) may also be carcinogenic. The topic of health and safety goes beyond our expertise at the Paint List, so please see the work of Monona Rossol and other experts for information.

A historical crimson of unknown composition - about what we find to be the case when "red lake" is mentioned in art history literature

PR9 and NR9- Different things!

NR9 is the old school Rose Madder

PR9 - Naphthol AS Red (one of several napthols). We were surprised to find PR9 in oil paints currently available on the market - especially because these are primarily found in Cadmium Red imitations, and their lightfastness is not that good. This pigment has only moderate lightfastness- it is given an ASTM II in oil but depending on the paintmaker's pigment supplier, it may only get 5's in tints on the Blue wool scale. In watercolor, Bruce MacEvoy calls it very fugitive, and notes it is ASTM III in watercolor. However, his tests showed even worse performance- something like IV. We primarily noticed this pigment in student lines, and to make matters worse the PR9 was sometimes found alongside other pigments that also performed poorly.

Once again, Monona Rossol's writing raises awareness about potential serious health issues that could arise with this pigment, as it may metabolize to a carcinogen, so please consult her writing for more.

NR9- Madder Lake - Rose Madder Genuine. Four oil colors are currently made with this historical pigment. This is a lovely historical hue. We had a vintage tube, and it had a sort of "glazes only" quality. It was sometimes streaky but a rather high chroma pink (nothing like PR122). Something like a milky transparency, a transparency in masstone. The light gets around the edges when looking at in masstone, and this shows that filmy quality.

Depending on exactly how it is manufactured, its properties may vary. Pigment NR9 is sometimes called Alizarin or Purpurin (genuine Madder Lakes contain both Alizarin and Purpurin), and there is some interesting literature on how the purpurin fades out (weirdly, despite the resemblance to the color name purple, purpurin is an orange color which is fugitive).

Reports on the lightfastness of natural madder in oils vary tremendously. Virgil Elliott notes that the thickness of its application may affect its permanence and that it may fare better unmixed and at full strength rather than a glaze. How this pigment is manufactured as well as the precise process may matter a lot. Some vintage paints in oils from Winsor and Newton are surprisingly beautiful with a filmy/milky pink consistency. However we would not rely on this as a lightfast pigment. Agreement is pretty uniform that genuine Rose Madder fades.

It requires a high amount of oil to turn it into an oil paint and tends to be a slow drier.

Vintage Winsor and Newton Rose Madder. This is one of the deeper versions of genuine Rose Madder that we've seen in oils.

Mistaken Identities -PR19 or PV19?

A Frequent Pigment Mixup

PR19 but Also see PV19 - Quinacridone Rose. This is an interesting case of a pigment that might not exist. If you see PR19 double check, because it might be a typo meant to be PV19 instead. This color is listed on artiscreation as Arylide Maroon, and very interestingly, it simply lists this pigment as obsolete without much information at all.

Its seems that "PR19", when found as a pigment listing for a paint, may actually be a typo in some cases for PV19. When we checked, we saw that it was listed for St. Petersburg Masterclass oils as well as a Utrecht magenta blend which is very likely PV19. In regards to Utrecht, their brochure listed PV19 while the Blick site stated PR19. Our guess in the Utrecht case is that it's PV19 Rose - the pink version. See PV19 in the violet section, as this pigment can be either red or violet.

M Graham Quinacridone Rose is PV19. A couple of pigments like PV19 have two natures-- one rose and one violet. So while the pigment code PV would suggest pigment violet, this version of PV19 looks red or magenta

Some Quinacridones that look red actually actually have a pigment code listed under the violets- like PV19

Sometimes the red version of PV19 is incorrectly listed PR19. PV19 comes in a pink form, often called Quinacridone Rose

Roguish Reds

Pigments you may wish to avoid

Has anyone really made enough jokes about the Rouge Rouges? (English Rogue -- pronounced like "roag") and french Rouges, meaning reds? Probably not. But that is unfortunate. The English noun rogue means, "a person whose behavior one disapproves of but who is nonetheless likable or attractive" or, "(of an elephant or other large wild animal) living apart from the herd and having savage or destructive tendencies." So now that you have the image of a runaway elephant in mind, we can turn to its use as an adjective, "denoting a person or thing that behaves in an aberrant or unpredictable way, typically with damaging or dangerous effects." That would be apt here, as these reds can be beautiful but tend to harbor bad lightfastness, which may only be found out later. Where this begins to be relevant is that moment when, like me, you might find have found yourself buying an exceptionally beautiful Japanese watercolor full-pan set only find out those beautiful reds were none other than the inadequate PR48:4 or even perhaps the rotten Lithol Bordeaux PR63:1. Needless to say those paints will be replaced.

PR22 - Naphthol Red Bright (one of several Napthols). Not recommended for artist's paints due to poor lightfastness. This dips into the bottom category of ASTM III, which is below the dividing line for even for other peoples' standards in paints. Thankfully we did not see it in oil, but we were shocked to see it in no less than 10 commonly available acrylics. However we mention it here as some artists combine oil and acrylic workflows in their paintings.

Another problematic red, we found a caution in Monona Rossol's research about potential serious health issues that could arise when this pigment is metabolized, as a derivative may create a carcinogen, so please consult her writing.

PR23 - Naphthol Red Dark. A pigment whose lightfastness descends to ASTM IV- not suitable for artist paints- also flagged for potential health problems. It is currently found in six acrylic paints made by major manufacturers and at least one watercolor.

In Monona Rossol's writing, this is a suspected carcinogen, and has caused kidney damage in rats, along with metabolizing to cause something related to methemoglobinemia, so please consult her work for more information.

NR31- Dragon's Blood. Uncommon in artist pigments, and not found in oils, but it can be found. A. Gallo writes, “Dragon’s blood is a surprising red made from the resin of the Daemonorops draco plant and other rattan palms. This exotic red was used by the early Greeks, Romans and Arabs in art and medicine." ASTM IV, so not lightfast. It is based on a tree resin.

PR48:4 - Permanent Red 2B. It is a great irony of life that so many things named "Permanent" are just the opposite. This color has moderate to inadequate lightfastness and may fade to a 5 in tints depending on the supplier. Surprisingly, it is found in three oil paints by major paintmakers.

Monona Rossol writes that this may cause methemoglobinemia and has more warnings about it in her writing on pigments which also apply to other forms of PR48 as well.

PR63:1 - Lithol Bordeaux. This Monoazo crimson pigment has inadequate lightfastness (as low as 3 in tints, and really not all that much better in other categories). It is found in at least one artist oil paint line despite the poor lightfastness.

In Monona Rossol's research we noticed a note about potential serious health issues that could arise when this pigment is metabolized, as a derivative may create a carcinogen, so please consult her work.

PR81:1 - Rhodamine 6G FIAT What appears to be a bright, chromatic pink, this one only showed up in watercolors. Unfortunately too low in lightfastness to be suitable for artist's paints. A sinkingly low ASTM IV. In addition it is an animal teratogen, maybe a mutagen (?), and possibly a carcinogen according to Monona Rossol's latest writing, and may have even worse inclusions, so see her work for more.

Pigments made into watercolor, including PR48:3, PR48:2, and PR63:1

Highlight: Historical Alizarin Crimson

PR83 - Alizarin Crimson (Genuine). The "genuine" part must now be added since the pigment is now discontinued and imitations already abound. This is a rich gem-like crimson that is has been incredibly difficult to replace. It is baffling that it is so difficult to replace exactly. Alongside its beauty, painters have been plagued with a quandary: what does one do about its terrible lightfastness? PR83 is often used as a fading pigment by which to judge the lightfastness of other colors- unfortunately Alizarin tends to loose its lightfastness that reliably. In addition to the fading this pigment has issues with cracking, which is less often discussed, but nonetheless reported to be an issue. It requires a lot of oil to turn it into an oil paint.

Another issue which many never thought to consider is that chemically, both artificial and natural alizarins are actually incredibly similar to cancer-causing anthraquinones. It may also cause allergies. Monona Rossol's work on pigments contains more information.

Alizarin Crimson was beloved in the 20th century, and many painting books recommended it despite its poor lightfastness. That issue seems to be even worse in watercolor than in oil. So, due to its performance it cannot be recommended, but in any case it is now in the process of actually disappearing by way of discontinuation.

In 2023 or 2024 it was phased out by pigment makers, however some paint companies still have supplies of this traditional mainstay. It is incredibly difficult to replicate this pigment, and part of its mystery is a brown note hidden in the crimson. It is a deep dark red, which is an area of the palette where painters can always use more pigments. Many companies have turned to PR177 as a permanent Alizarin. However, Virgil Elliott's tests revealed that in time PR177 also fades, despite the name "Permanent."

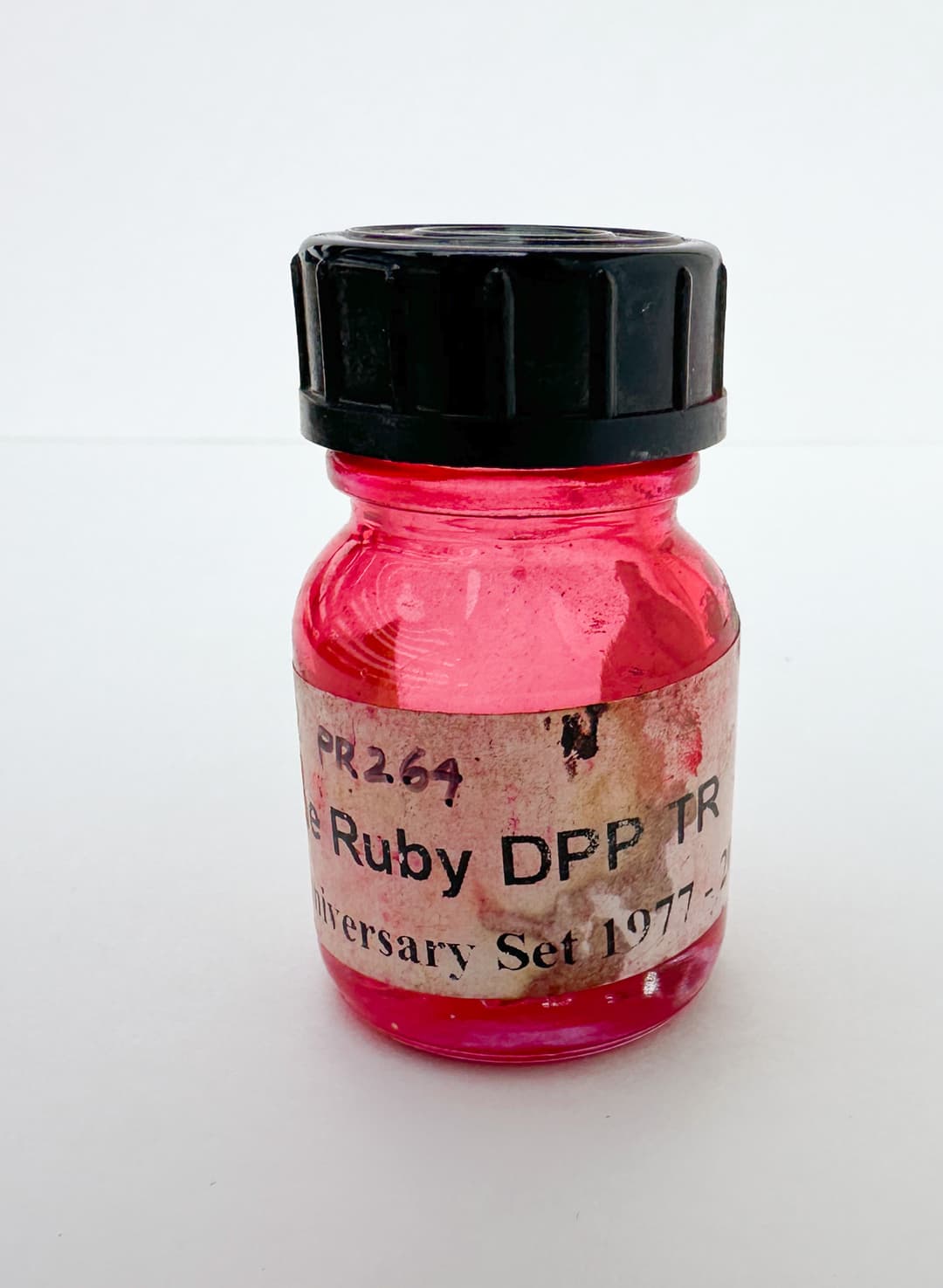

Some recommend PR264 Pyrrole Rubine as a replacement. Old Holland also has an interesting imitation blend to approximate genuine Alizarin.

PR83:1 - Synthetic Alizarin Lake. This is a less commonly listed variation of Alizarin Crimson, however artiscreation.com posits that perhaps actually it is this variety that is often found in tubes labeled PR83.

PR88 - Thioindigoid Violet. Speaking of extinct pigments, this plum color is also unfortunately no longer available. It has decent to good lightfastness.

Lacca Di Garanza historical pigment from Zecchi, historical Alizarin Crimson.

Alizarin Crimson

Now discontinued, previously a star of 20th century palettes, and still fades

Red Earths

Rock Solid Reds for Lightfastness

For natural red earths, PR101 and PR102, there are two main varieties: natural and synthetic. However these cover a huge array of colors and consistencies. The natural ones may have a bit more nuance, and many that we've tried have a large particle size (read grit). The synthetic ones, sometimes labeled Mars Red, can have an extremely fine particle size.

These are useful in all manner of mixtures- to complement blues, to mix flesh tones, to create deep dark passages at low lightnesses or to create glowing chroma. Along with other earths (see yellow earth and brown earth) these earth tones have played a central role in art history and human cultural production.

The names for red earths often derive from places where certain red earths were historically mined. Each place has a distinctive set of qualities which helped to form the traditional names. "Venetian Red" or "Pozzouli Earth" harken to places where these colors were found. A cannon has arisen around these names such that synthetic colors with similar properties may borrow from the geographic names, but unfortunately this is not a guarantee as there is no standardization. These names are discussed below and may apply to synthetic or natural earths.

PR101 - Synthetic Iron Oxide Red. Also known as Red Oxide or Synthetic Red Ochre. This pigment group includes a huge variety of synthetically made red earths, oranges and violet-browns. Particle size can vary considerably and with the synthetic version it can sometimes be very small- though this is by no means a guarantee. Some brands, like Williamsburg, publish guides to the grainyness of their colors, while other brands rely on the brand vibe to convey the degree of homogenization among their colors (for example, some brands are known to make very smooth colors overall).

The Artist's Guide to Health and Safety has more information about health issues associated with pigments which contain Iron. Her updated work can be found through her site.

The PR101s are a wide-ranging bunch, and they can be red, brown, orange, violet or even greenish. They are super lightfast. Sometimes the name Mars will be present in the paint name. Colors like Mars Red or Mars Orange will usually be made of pigment PR101.

PR101:1 - Red Hematite. This is a fairly rare pigment code to find. A subset of PR101.

In general the synthetic red earths tend to be powerful colors.

One of many versions of Synthetic Red Earth. This one is called Mars Red by Zecchi

A Wide Range of Colors, One Pigment Code

Synthetic Red Earth, PR101, comes in a variety of shades from orangish to reddish to nearly purple

PR102

PR102 - Natural Red Iron Oxide or Red Ochre. These can come in almost any color of earthtone (brown, red, orange, yellowish or even greenish). There is a lot of variety. Sometimes the particle size is a bit larger than the synthetics, but this is not a given. These are pigments of outstanding permanence and lightfastness.

Natural Red Ochres are associated with paints that tend to be fairly opaque. Sometimes natural red ochres have a character that is just not matched by a particular synthetic pigment due to various other naturally occuring components in the pigment. Sometimes natural colors are a bit more softened than their synthetic counterparts. For many reasons the natural versions of these pigments retain their charm.

Naming conventions in the synthetic red earths are often derived from art history and from their natural red earth counterparts (see also PR102, Natural Red Iron Oxide). Each name has a general pattern of what to expect from the pigment but there is no standardization.

Some issues could arise from working with Iron pigments, but we also saw a note about Silica (respiratory hazard) that could be in natural iron oxides, PR102. See the Artist's Guide to Health and Safety. The author's updated work can be found through her site.

All different colors of PR102

Another case of one pigment code, many colors.

The natural red earths PR102

Common Names for Red Earths, PR101 and PR102

A few names are common among synthetic red earths.

Transparent Red Iron Oxide: The most common name among PR101 paints. These colors tend to be distinct deep brown reds with gemlike transparency when thinned. They tend to be low in lightness and high in chroma for their depth.

Mars Red: The name "Mars" connotes that the earth pigment is synthetic. These are often powerful colors compared to natural earths. Some are opaque and about half do not have an opacity listed. Perhaps it is because some of the transparent versions tend to be labeled "Transparent Mars Red."

Mars Violet, Caput Mortuum: This is a synthetic earth violet or dark red. Like all PR101s these colors have excellent lightfastness and medium to low chroma. It will not produce bright tints like a synthetic violet would, but it makes some enchanting, subtle mixtures - good for flesh tones at times and also for realistic painting. Caput Mortuum is a related color name that actually translates to 'dead head.' These are low lightness red-purples, and many of them are opaque. In his work on Traditional Oil Painting, Virgil Elliot notes that Caput Mortuum requires a lot of oil, whereas Mars Violet is only listed as having an only moderate requirement.

Venetian, Pozzuoli, and Pompeiian Reds: All these are distinct, but their use in modernity varies. A group of colors that ranges through the warm red-oranges, these tend to be rather chromatic. Their natural counterparts sometimes have a large particle size, but whether this is mirrored in the synthetic varieties is not a given. They tend to be associated with a bit more of an orange, though some varieties will tint a bit pinker than others. Natural versions have more nuance in the transparency, but for some reason we tend to think of these as opaque. They are gentler tinters than other red earths. Overall lovely to work with. Again this varies from brand to brand. Among current paints, most of the synthetic versions are opaque, while the natural versions tend to be listed as semi-opaque or semi-transparent. In Traditional Oil Painting Virgil Elliot notes the rather lean oil requirements of Venetian Red, which make it more suitable for the lower layers of a painting.

English Red, Light Red: This color grouping tends to be a little redder (less orange) than the Venetian Reds, but it varies from red-orange to red. Many of the synthetic versions are opaque and have good covering power. The term "Light Red" in earths refers to a similar color and opacity. The color of Light Red is a relative term as many of these are not light at all, but rather a kind of burnt red orange. While the synthetic Light Red paints tended to be opaque, the natural versions tended to be semi-opaque or semi-transparent. English red is named for a variety of red ochre from England that became famous.

India Red, Indian Red, Persian Red: This grouping tends to refer to very intense, opaque reds that lean a bit cooler (at least for red earths) with a lower lightness and high covering power. This is often an intense opaque red earth with a lot of presence. They tend a bit redder than many Venetian reds and some are quite deep. Even among natural Indian Reds (PR102) most are opaque. Indian reds do not require as much oil to make into a paint, which may make them more suitable for the lower layers of a painting.

Burnt Sienna: One of the quintessential artist's colors, Burnt Sienna has diverse applications in all styles of painting from flesh tones to landscape to abstracts, this warm brown is everywhere. The same paint name is also found among the PBr7s, as well as many natural red earths, colour index PR102. Burnt Sienna is a warm middle brown which often shows rosiness in tints. It It is brown and a red at the same time. Burnt Siennas range from transparent to semi-opaque, however it is also possible to find opaque versions. Natural versions (PR102) are often named French or Italian depending on their origin and may have larger variety of particle sizes.

Mars Brown: Even though this is a PR101 (pigment red), they are sometimes brown. These colors tend to be intense, and it is fairly common for them to be opaque. Perhaps this is because the transparent versions tend to get labeled Transparent Brown Oxide. This color requires a lot of oil to make it into a paint.

Terra Rosa: A red with a faint purple note, these tend to be lighter and redder than Mars Violets/Caput Mortuum. The ones we've tried have tended to be powerful and opaque.

Orange Oxide: Despite being made of PR101, these paints are orangeish. Transparent versions get named Transparent Oxide Brown. Among the Orange Oxide PR101s, it is a little more common to see transparency.

There are other names besides these, but those are some of the major categories. These categories may also be applied to similar colors made with brown earths (PBr7) as well.

A variety of PR101 and PR102 Red Iron Oxide pigments from L. Cornelissen & Son

Historical Reds

PR104 - Molybdate Orange, Chrome Orange, Chrome Red, American Vermilion. Currently made by Rublev, this is an bright orange that is also toxic -extremely toxic. It contains Chromium VI. Please see the Artist's Guide to Health and Safety for more information about health issues associated with Chrome and Lead. The author's updated work can be found through her site. This color has mostly been discontinued, but Rublev's version is stated to have "silicate-coated (encapsulated) grade with very good lightfastness." However it is toxic and can easily be substituted.

PR105 - Red Lead, also called Minium or Surik. Very poisonous. A color which was popular historically. Rublev carries this as an oil paint, and it is one of the few paints of theirs to contain an additive as it has a short shelf life (as in maybe several months) when made into oil paint, and the additive will extend it a bit. This color is very toxic (Natural Pigments says to use utmost care to avoid exposures to this pigment- see their site for more details and as always be sure to do your own third party research). The dry pigment is reported to be reactive, and light may blacken it. However it does seem that binding it in oil may have some sort of protective effect. Even in oil it may have some sensitivities to the environment and may also perform poorly in mixes, though we have not verified this.

More information on hazards from lead pigments can be found in the Artist's Guide to Health and Safety. Her updated work can be found through her site.

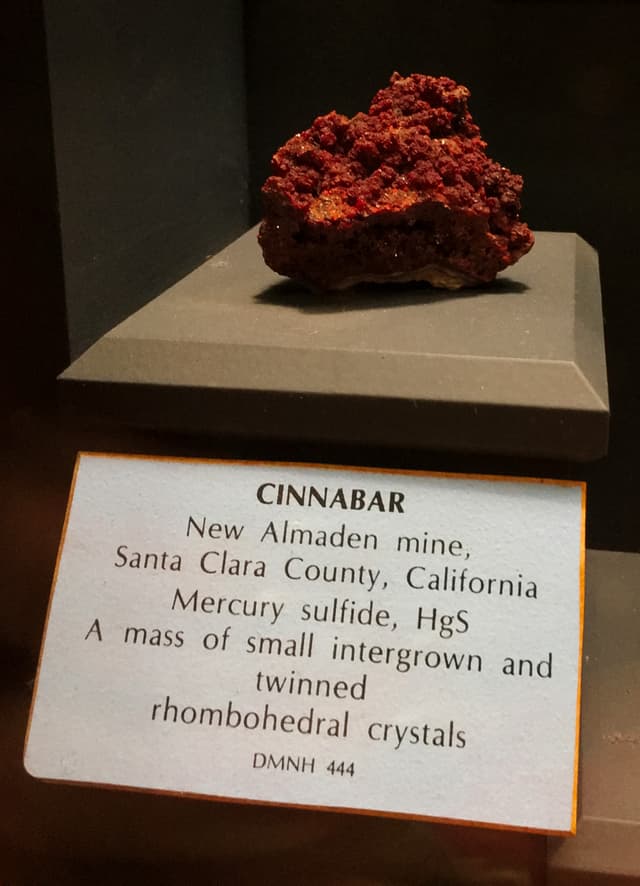

PR106 - Vermillion (Genuine), Mercuric Sulfide. A bright red indistinguishable in masstone from some cadmium reds, however it mixes a bit differently and tends to be semi-opaque. The natural mineral is called Cinnabar. Debate about its lightfastness has tended to be one of those things which "springs eternal". We were fascinated to see lightfastness tests from the legendary Gunzorro (one can find his vermilion tests here). Similar findings were echoed independently by Virgil Elliott. Unfortunately this pigment which has captivated painters does indeed seem to darken with enough light exposure. Whether it is because of a wet or dry process or adulteration with another pigment would require lab testing. We have heard that the sometimes-quoted ASTM designation of I has to do with the length of the ASTM exposure, and that perhaps were the exposure a bit longer vermilion would undergo the blackening that it so often exhibits.

Perhaps notably, Natural Pigments mentions that glazing madder lakes over Vermilion may help to mitigate this tendency to darken. There is discussion that the way it is manufactured may make a difference to its lightfastness as well as a note that the natural mineral may be better than the manufactured versions. This is one of the physically heavier pigments.

Controversy also (strangely) rages over just how toxic it is, but we would err on the side of caution and list this as a toxic pigment. Furthermore, Monona Rossol in her work on pigments notes that it may sometimes be contaminated with lead. More information on hazards from mercury as well as lead pigments can be found in the Artist's Guide to Health and Safety.

Several different color varieties of this pigment may be found depending on where it was mined or how it was manufactured. Cinnabar is the name of the rock form of this pigment, while genuine Vermilion is the name of the paint. Famous mines were in Monte Amiata. It is rumored that the finest qualities of real vermilion have not been available for a very long time, at least not since the closing of the famous Monte Amiata mines in Spain.

It has become difficult to ascertain the quality of various tubes of Vermilion as they are sometimes cut with fillers or may even have Cadmium Red standing in for the genuine pigment. It's said that some of the duller versions of vermilion may be substandard representations of what this pigment can be, or perhaps used to be. On the other hand there are some brilliant cadmiums that are difficult to distinguish from the better versions of vermilion which poses a different challenge. There may be some simple studio tests for distinguishing genuine vermilion from cadmium.

Also it is said that genuine vermilion is very slow drying, which is interesting because it has rather lean oil requirements when made into a paint, according to Virgil Elliot's book In Traditional Oil Painting.

In terms of hue, the great Gunzorro once described PR106 as somewhere between red earths and the cadmiums. There are at least two different main color groupings within Vermilion. The two colors of vermilion tended to be the orangey, and the Chinese, which was a cooler red. The former color is associated with the Imperial kind (or Monte Amiata Imperiale) which made warmer pinks in tints.

Genuine Cinnabar, Cinabro Originale from Zecchi Pigments

Genuine Vermilion

Vermilion in rock form, A possibly genuine vintage tube of real Vermilion

Cadmium Reds

High-Performance Lightfast Reds with Exceptional Covering Power

PR108 - Cadmium Red. Cadmium Selenosuphite or Cadmium sulfoselenide. A smashing pigment that is opaque, high chroma, and lightfast, though please handle according to best practices for toxicity. The color can range from red-orange to a rich bright red, to a moody maroon. Classic Cadmium Red is available in Light, Medium, and Deep and gets solidly excellent marks for lightfastness. Bear in mind though that prolonged exposure in direct sunlight (i.e. for years) will eventually darken them. (For a super-lightfast and sadly extinct specialty version of Cadmium Red see below). One of the great things about the opacity is a hard to define quality in the presence of these colors- their opacity sends the color back to the eye with a centered, authoritative confidence.

A handful of Cadmiums can create a built-in rainbow section of the palette. Of course interstitial notes can be mixed between them, and we recommend this for beginning painters. However at full strength a series of cadmium reds and red-oranges can create a pleasing representation of the palette colors at high chromas. From this gorgeous series of progressively warming notes the cadmium reds flow seamlessly into the cadmium oranges.

Cadmium is a carcinogen that also causes kidney damage, so we always treat it with respect as a toxic pigment. More information on hazards from cadmium pigments can be found in the Artist's Guide to Health and Safety. Her updated work can be found through her site.

One potential painting-related drawback is if a person is looking for high chroma tints-brighter tinted red-oranges for example. Cadmium Red can be a bit chalky in tints, however a couple of varities we tested were a bit brighter than the others. The note of desaturation it takes on is not necessarily a bad thing in realistic work. At full strength, it is one of the most chromatic colors at several hue angles.

The cadmium reds are one of the main pigment groupings for oil paints. Most cadmium reds will bear the pigment code PR108, however some will have PR108:1 as a sort of less expensive version. We have read that the degree of redness relates to the amount of selenium as well as differences in heating.

Also, as a quick reminder that lightfastness does not mean the same as weather-fastness. Cadmium reds are sensitive to moisture.

This pigment spans red-orange to cherry reds to deep purpleish maroons. Paint makers will name their colors Light, Medium, or Deep to distinguish the major hue groupings. On either end of the gamut one may find Cadmium Red-Orange or even Cadmium Maroon. For more on cadmium reds, see these articles with paint comparisons: Cadmium Red Deep and Medium, and Cadmium Red Light and Medium.

There is some controversy over the degree of toxicity of these paints (artiscreation lists PR108 as a B, meaning there is toxicity), and always we err on the side of caution. We treat them with the respect we give to toxic pigments.

One interesting thing is that in his work on Traditional Oil Painting Virgil Elliot specifies cadmium reds and the related cadmium-barium reds as having rather lean oil requirements, which relate to their use lower levels of an oil painting. If additional driers have not been added, they do tend to dry slowly.

PR108:1 - Cadmium-Barium Red, a cadmium red made in a more inexpensive way. Seen sometimes in student brands. The health warnings for cadmium red apply also to PR108:1. See above.

Vintage jar of Cadmium Red Light from Bocour

Cadmium Reds

High Chroma Lightfast Reds

Napthol Red

PR112 - Naphthol Red AS-D (one of several Napthols out there). This pigment crops up everywhere, and it is gorgeous in tints, but not nearly as chromatic as some of the other reds when lightened. Still this makes a lovely ingredient for certain pinks.

We were shocked to find out in Monona Rossol's writing on pigments that it has a similarity to dyes that cause cancer, may metabolize to a carcinogen, and cause methemoglobenemia as well as other problems-- see her research for more. It is often found in cadmium replacements, so its own toxicity is interesting to note.

Unfortunately Napthol Red PR112 also fades more than we would like to see in an artist color. Also, in oil this color showed surprising reactivity with lead white and will shift color in minutes. See Golden's Lightfastness Testing in Oils for more.

I used to absolutely adore this color and I only wish it were more lightfast. It makes the most interesting red tones in skin for portraiture- a lyrical red-pink with an orange hint. It was one of my most favorite colors that I used to use as a student before I found out it was not lightfast.

Napthol Red in oil

An Extinct Superlightfast Red

Mysterious Mercadmium

PR113 - Mercadium Red. An extinct pigment which deserves special note as a super-lightfast red. We'd call it very toxic (artiscreation gives it a D meaning, "Extremely Toxic, only attempt working with these pigments (especially the dry form) in laboratory like conditions with proper safety equipment "). Plus more information can be found in the Artist's Guide to Health and Safety for pigments containing cadmium and mercury (and possibly barium depending on the formulation). Her updated work can be found through her site.

While cadmium reds have excellent lightfastness in general, this one is famous for having even more lightfastness in a test of extended light exposure done by Virgil Elliott. At one time Vasari offered this as a color, however they no longer carry it.

Vintage Permanent Pigments Mercadmium Red PR113

Quinacridone Magenta

PR122 - Quinacridone Magenta. This is a staple pigment for any palette- able to get higher chroma light reds and red purples when mixed with white than many other pigments. It creates smashing purples and lovely tints, and it has excellent lightfastness depending on the supplier. It can also help to tune reds towards crimson.

This was the first addition to my palette after painting with a strict limited palette for some years. Quinacridone Magenta opened up new areas of the gamut for red-purples. I now paint with a range of Quinacridones at various hue angles in addition to this one, but if I could only choose one, this would be it. This color is an exceptionally cool magenta which is useful in tints and also in mixes for purples and fuchsias.

Of the available options in the magenta range it has some of the most promising lightfastness, however this may be something to look into and test from brand to brand. The Artiscreation lightfastness scales show some variations. One hopes to find the versions which are excellent and receive the highest ratings.

Whether painting with a split-primary palette or a very abbreviated power-palette of just a few CMYK colors, Quinacridone Magenta is one of the most important pigments. A crucial component for purples and red-violets.

Like many transparent colors it tends to be a slower drier.

Quinacridone Magenta, PR122, a palette staple

More Reds

PR123 - Perylene Scarlet. Moderate lightfastness, not lightfast enough in tints to suit our liking. Not recommended.

Monona Rossol notes that it has an anthraquione-like structure (potential for being a carcinogen) as well as a risk for inhaling the dust. Please see her work for more.

PR144 - Azo Condensation Red. Looses just a bit of lightfastness in tints.

PR146 - Naphthol Red AS. Somewhere between decent and fugitive, this pigment is not recommended. Additionally, in Monona Rossol's research it states that when this pigment is metabolized, a derivative of PR146 may create a carcinogen, so please consult her writing.

PR149 - Perylene Red, Anthraquinone Red. One of several. Transparent. Not recommended due to moderate lightfastness- might go as low as a six.

Monona Rossol notes that it has an anthraquione-like structure (potential for being a carcinogen) as well as a risk for inhaling the dust. Please see her work for more.

PR166 - Azo Condensation Red. Not recommended, lightfastness is moderate.

PR168 - Anthradquinone Scarlet. This color was recently discontinued, but may be available again for a time. It's a beautiful bright red with a note of orange in it, transparent and useful in madder approximations. Old Holland has several interesting blends made from this color. The high lightfastness marks- hard to find in a transparent red- may or may not translate to oils. It's a slower drier.

It may be carcinogenic, as it is similar to anthraquinones that have been listed as probably carcinogenic (please see Monona Rossol's research work for more information.

In watercolor it seems to behave fairly well for lightfastness. However in oil it is more of an ASTM II instead of ASTM I but it may vary by brand. Some sources give this color solid 8's (highest marks) on the blue wool scale.

PR170 - Naphthol Red AS (one of several). This is a gorgeous red that made some stunning pinks, but lightfastness can vary widely. In general its is not recommended due to its moderate (meaning not good enough) lightfastness. There appear to be two forms of this pigment, and one is more lightfast than the other.

May be related to health problems, such as methemoglobinemia, as well as some other things. See Monona Rossol's work for more.

PR175 - Benzimidazolone Red HFT. Sometimes called Benzimidazolone Maroon. The lightfastness is reported to be good, though itmay loose just a little in tints depending on the pigment supplier.

PR176 - Benzimidazolone Carmine. Lightfastness may be decent to moderate.

Quinacridone Magenta

A rockstar magenta that leans blue

Fascinating Crimsons

PR177 - Anthraquinone Red, This is a widely used red in "Alizarin Crimson Permanent" and other substitutes for fugitive Alizarin. It's very transparent.

This color, along with other similar anthraquinone pigments, may be carcinogenic. While this specific pigment has not been tested, other similar pigments have been listed as "reasonably believed to be carcinogenic." Please see Monona Rossol's research work for more.

Even though it received an ASTM I designation, it is reported to eventually fade. In Virgil Elliott's long term lightfastness tests revealed interesting things that go beyond the regular ASTM testing from the 1980s. He performed many interesting tests, and one of his six-year test panels can be found here.

So, while some pigment suppliers make a product that can receive all 8's (excellent) on the blue wool scale, this pigment does appear to fade eventually with long-term exposures which go beyond usual lightfastness testing.

This is a rich, lusterous, sparkling red with depth in a helpful area of the spectrum. It is transparent and chromatic at a low lightness. If you use this color it might be helpful to do your own lightfastness tests since among suppliers it seems to vary a bit.

PR178 - Perylene Red (distinct from Perylene Maroon). Lightfastness is decent to moderate. May be better in watercolors, however it may fade in tints.

Monona Rossol mentions that this pigment has an anthraquinone-like similarity (potential carcinogen) may cause methemoglobinemia, and be associated with health problems- please see her work for information about powder/dust hazards.

PR179 - Perylene Maroon. Valuable as a transparent red. In thicker glazes it can appear similar to Anthraquinone Red (PR177), but in thinner glazes a different nature is revealed. It feels like a cross between Alizarin Crimson and Quinacridone Violet, and has a tiny bit of desaturation to it. A helpful color where deep, chromatic reds and violets are needed. Some versions are very slow drying, but worth it. This color tends to be transparent and is reported to have excellent lightfastness.

This color has a structure that is similar to the anthraquinones (possible carcinogens) so please consult Monona Rossol's work for more information.

PR184 - Permanent Rubine F6G. Not recommended due to moderate lightfastness. Ranges from decent to fugitive.

PR187 - Permanent Pink FL. This is the famed Carl's Crimson. A LF rating of II. This is a fun red that makes some interesting tints and blends. However the ASTM II rating is not as high as we'd like to see, so we would not wholesale recommend it based on moderate lightfastness.

PR188 - Naphthol Scarlet Lake.

In Monona Rossol's work on artist safety this pigment may metabolize to create a carcinogen, and can possibly cause methemoglobinemia. See her writing on pigments for more information.

PR202 - Quinacridone Crimson. This is stellar color which has at least two different natures. When I first found this pigment, I fell in love with the bright purple-magenta color since certain forms of it are reported to be very lightfast (some have solid 8's on the blue wool scale). It is fairly rare in oil paints. Since then I have had trouble finding the more purple version as it was replaced in the paint line where I had found it by the more magenta kind.

This is a color I'd recommend as a standalone pigment- not necessarily for mixing, but rather for its beauty on its own.

PR206 - Quinacridone Burnt Scarlet. Unfortunately this was recently discontinued. It made an interesting complement to certain greens, and was a fascinating color in its own right. We explore this pigment in an article on Discontinued Pigments.

PR207 - Quinacridone Scarlet. A gorgeous light red which was also recently discontinued. This red had good lightfastness and was smashing in tints. Quinacridone Scarlet has a delicate quality reminiscent of PR209. This pigment was part of an article on Discontinued Pigments.

Quinacridone Red, PR209

PR209 - Quinacridone Red. We love this color so much that the ASTM rating of II just hurts to see. If it's from a supplier where you can avoid those blue wool scale 6's that's one thing, but this beauty seems to have a definite risk of fading depending on the supplier. This color is a merry red that makes gorgeous tints. It has transparency to it. May be better in for lightfastness in watercolor than in oil.

PR214 - Fastogen Super Red 2R. Decent to excellent lightfastness.

PR221 - Pigment Red 221. This is listed as ASTM II, so that is a bit lower than we like to see.

PR233 - Chrome Tin Pink (Potter's Pink). This is a wild color in artist's oils which is fairly rare. It is a dull pink- the dry pigment looks a lot more lively than the paint. However it is reported to have good lightfastness. More often found in watercolor than oil.

PR242 - Disazo Condensation Scarlet. This is a fascinating orange-red which is fairly rare in oils. It makes beautiful high chroma tints. It also has good to excellent lightfastness. However, the version by Schmincke Mussini is a slow drier.

**PR251** - Pyrazolo-quinazolone scarlet. Good to excellent lightfastness.

Quinacridone Magenta, PV19. While not listed among the reds, this pigment can be made into a paint which almost looks like PR209 - Quiancridone Red. PV19 has two forms, the reddish one shown here and a more plum colored violet.

Pyrrole Reds

Gorgeous high-performance, lightfast red PR245

PR254 - Pyrrole Red (more below) and its companion,

PR254 is Lightfast, soaring chroma, and used on Ferrari's. What more could a person want. This is actually a fairly good approximation for certain brands of Cadmium Red Medium. It is a very intense color. We did a deep dive on Pyrrole Red. We made comparisons to cadmium red, explored its complements, and also its use in mixes.

PR255 is an equally awesome, though lesser known, Pyrrole Scarlet. Why would you want PR255 in addition to PR254? It makes smashing, chromatic tints that lean a little oranger than PR254. We love this color. Excellent lightfastness.

For the more magenta Pyrrole Rubine PR 264, see below.

Intense Pyrrole Red, PR254

Ruby Reds, some chromatic some dusty, some crimson

PR259 - Ultramarine Pink. An enchanting red-purple with excellent lightfastness. This is a super fun color to add if you have already explored most other areas of the palette. As soon as we tried this pigment there was no going back, as one cannot have too many lightfast red-purples.

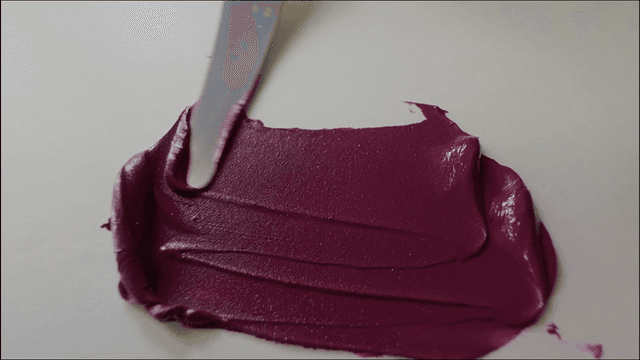

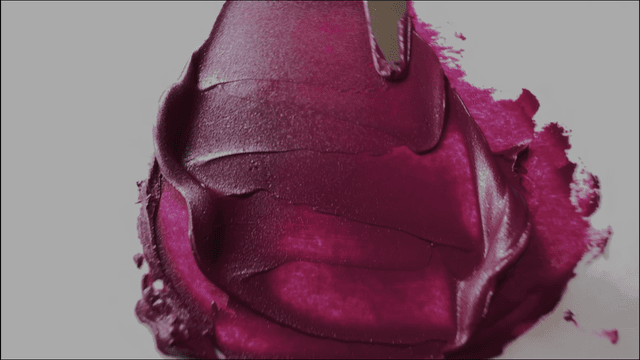

PR264 - Pyrrole Red Rubine. Excellent Lightfastness. This is recommended by some as an alternative to Alizarin Crimson.

PR272 - Pigment Red 272. Also a pyrrole, this one has good to excellent lightfastness.

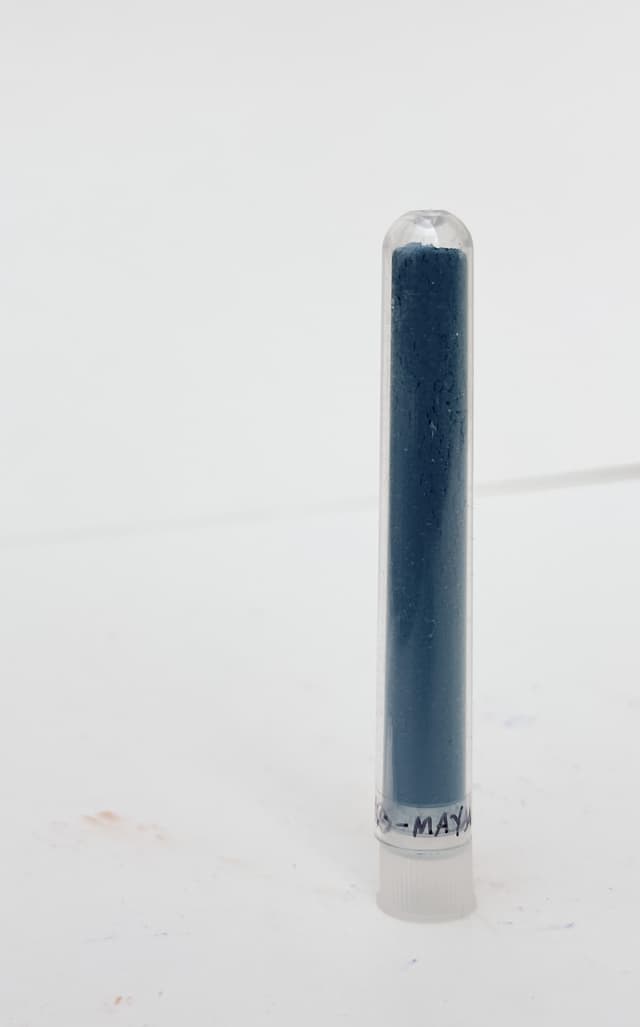

PR287 - MayaCrom Red R2051; related to the modern discovery of Maya blue.

PR290 - Sicopal Red. Fairly rare in artist pigments. Said to have excellent lightfastness. An orangy red used by Roman Szmal and also Cobra water mixable oils. Non-staining, granulating.

PR298- YInTiCo - This fabulous color is lightfast, has opacity, and is an enchanting raspberry. It also has infrared reflective properties.

Orange Pigments

A category with rounded edges

Where does orange begin and end? This is a pigment category that borrows a bit from yellow (some PY pigments are definitely orange) as well as its other neighbor, reds (red lead fits right in). This is a category without a ton of lightfast options, and only a handful of the pigments used in artist's paints are really fit for them in our opinion.

Again the pigment listings begin with a few not-fit-for artist-paints pigments.

PO5 - Hansa Orange RN. Sometimes labeled Permanent Orange, unfortunately it is not permanent at all, and has moderate lightfastness. It's currently offered in oils by two paintmakers. Sometimes the blue wool ratings show fading as bad as 4 in tints, and even the better versions are still looking at 5's and 6's. In her latest work, found via her site Monona Rossol mentions that this is listed as a carcinogen and also has toxic impurities.

PO13 - Benzidine Orange. Low lightfastness and also toxicity issues. Monona Rossol writes that it may be contaminated with PCBs --also please see her work regarding issues with a cancer causing compound (we advise artists to research benzidine in artist pigments). Unfortunately, a reputable artist pigment manufacturer uses this as a single-pigment imitation of Cadmium Orange. It also crops up in a handful of convenience blends- at least six- by another paintmaker. This color has shockingly low lightfastness in tints, as low as 3 on the Blue Wool Scale.

PO16 - Benzidine Orange. We advise all artists to research Benzidine in artist pigments regarding toxicity as it is serious. Monona Rossol's work on safety and artist pigments mentions that along with being contaminated with PCBs there are concerns about cancer causing chemicals. This color is actually used by a modern paintmaker in oils. It has abominable lightfastness and is reported to fade to a 2 or 3 on the blue wool scale.

Even though oranges may be mixed from reds and yellows, there are times one wishes for pure orange- perhaps for complementary mixing or for the highest chroma the painter's gamut can offer.

For a high quality orange, genuine Cadmium Orange is surprisingly vital for this role as it brings both knockout chroma as well as opacity from the marigold notes to bright orange.

A merry array of oranges

Cadmium Oranges

PO20 - Cadmium Orange (genuine)

Genuine Cadmium Orange, PO20, is surprisingly difficult to emulate or replace. A gorgeous, opaque, high chroma range of oranges. In discussions revolving around cadmium alternatives the lack of a suitable orange is acutely felt. When painting realistically a range of less chromatic oranges can absolutely be mixed from cadmium yellow deep and Cadmium Red Light. However there is actually a chroma boost from cadmium orange that is hard to match. It was years into our painting journey when we realized just how irreplaceable this color is, and once you really begin to study the chroma difference, it's hard to go back. (This is sometimes becomes especially clear in a medium like gouache). The opacity and overall character of cadmium oranges make them a wonderful addition to the palette.

However do handle with care and research the proper precautions as it is made of cadmium, a carcinogen which also causes kidney damage, so handle appropriately. In the Artist's Guide to Health and Safety Monona Rossol writes about the hazards of pigments containing Cadmium as well as Selenium.

This is a pigment which requires a high oil content- something to keep in mind if painting in layers. They do tend to dry slowly unless of course driers have been added.

Cadmium Oranges come in several color notes from a near macaroni orange to middle orange to red orange. More on Cadmium Orange can be found in our brand comparison in oils.

PO20:1 - Cadmium-Barium Orange, a version of cadmium orange that is less expensive to make. The same health warnings apply (see above).

Cadmium Oranges

PO20

A surprisingly necessary pigment for a range of high chroma opaque oranges

More oranges

PO34 - Pyrazolone Orange. According to Monona Rossol's work, this is a very concerning color and one which is likely carcinogenic. We advise all artists to research benzidine in artist pigments for toxicity. Surprisingly this color is used by at least three major paintmakers in oil as single-pigment color. Depending on the supplier the pigment ranges from inadequate lightfastness to poor, and even in the better ratings it's not that good. It's also found in blends by about six paintmakers and sometimes it is paired with other pigments that also have lightfastness issues. Artiscreation notes that Lightfastness may be slightly improved in redder versions. However the performance is reported to be not very good. Unfortunately several paintmakers use this color in their paints.

PO36 - Benzimidazolone Orange HSL. Offered by four major oil paint manufacturers as a single-pigment color and that increases to about six companies when it's found as part of a blend. The lightfastness for this color varies widely according the supplier. It would be advisable to do lightfastness tests if it is a color you like to use. From some pigment suppliers the lightfastness is excellent, and for others it is merely moderate. Williamsburg describes their version as, "Strong, somewhat sour, tomato-like red orange," and cites the ASTM I rating.

Monona Rossol's work mentions that this is one of the pigments which may metabolize to cause methemoglobinemia-- please consult her work on pigments for more information.

PO36:1 - Quite possibly a variant of PO36 used by Michael Harding. See above for the same health cautions that apply to PO36.

PO43 - Perinone Orange. Moderate lightfastness, best to do some research if this pigment is part of your workflow. Only one major manufacturer uses this as single-pigment paint in oils, however five other paintmakers have used it in a long list of blends. Lightfastness can dip to a five on the blue wool scale in some cases, so best to do one's own tests. Please take extra caution if using the dust -- consult Monona Rossol's work for more.

PO48 - Quinacridone Burnt Orange. Unfortunately this interesting pigment has been discontinued, however as of recently it was offered by four major paint brands, and may still be found in a few sap green blends. Along with Quinacridone Gold, PO49, it was smashing for botanicals and all kinds of realistic subjects. It's like a supercharged, chromatic, rich, dark stained glass-like color, like a super-charged chromatic Burnt Sienna. It has excellent lightfastness in oil.

PO49 - Quinacridone Gold. Radiant, especially in mixtures to create botanical greens. A complex transparent yellow. This color is unfortunately extinct, and there was great mourning when it left the art supply store shelves especially in the world of watercolor, though it was available in other binders. A wonder from the the automotive industry, which we still hope will bring it back someday, there isn't anything exactly like it. We've done some tests on pigments which can come close. If you're purchasing it, be on the lookout for imitations. Real Quinacridone Gold is interesting to try.

PO59 - Pigment Orange 59. Also known as Paliotol® Orange, this color is a transparent golden yellow orange and has excellent lightfastness. Currently it is offered by just one paintmaker in watercolor.

PO60 - Benzimidazolone Orange HGL. Used mostly in industrial application, described as a reddish orange. Slow drying but excellent lightfastness. Monona Rossol mentions that it may metabolize to an aniline. See her writing for more information.

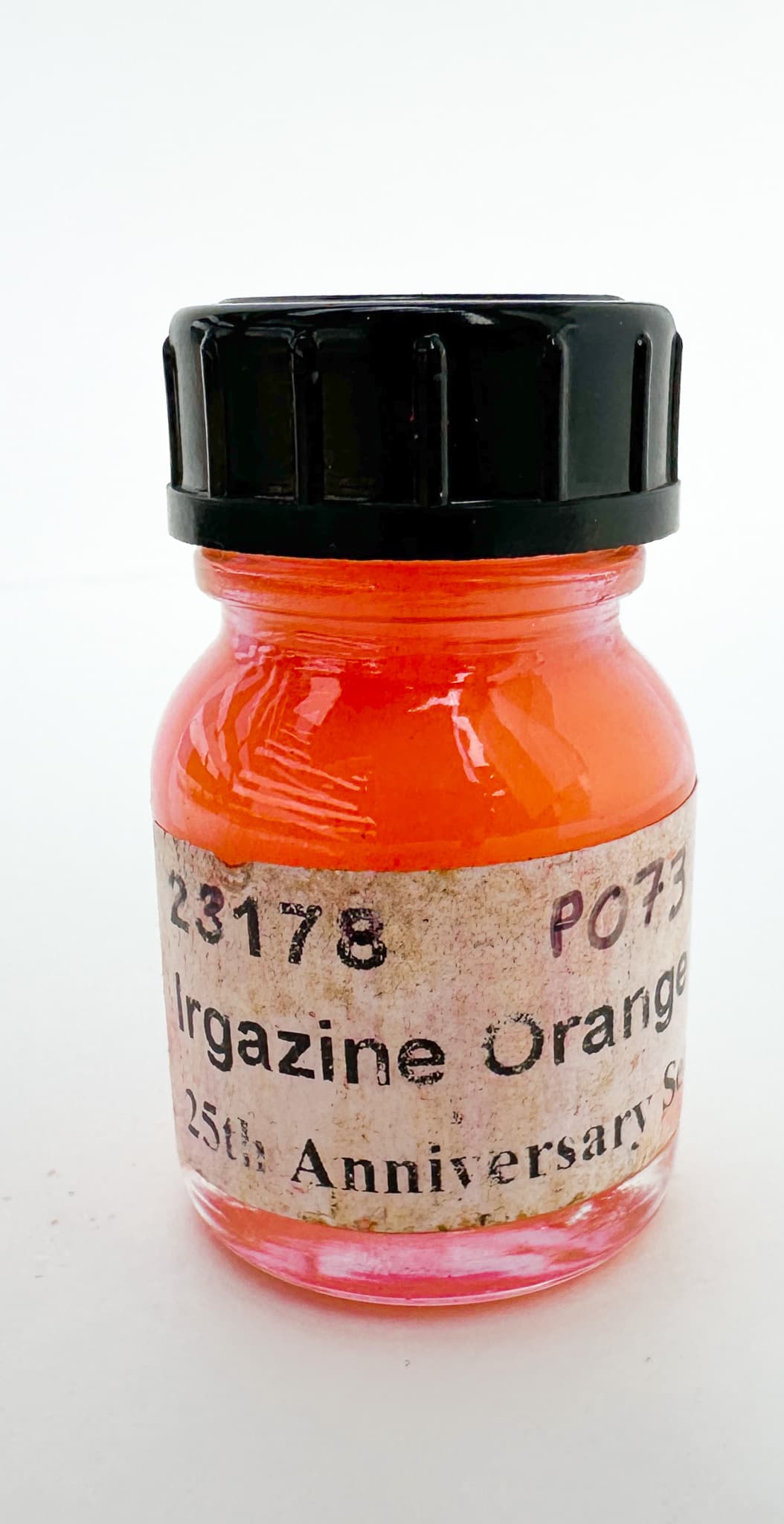

PO61 - Isoindolol Orange, also known as Irgazin® Orange L. This color has moderate to excellent lightfastness depending on the pigment supplier, so one may wish to do one's own lightfastness testing. It's offered by one paintmaker in oil and acrylic, and turns up in a few blends in watercolor.

PO62 - Benzimidazolone Orange H5G. This is a color that turns up in a handful of the attempts to replace Cadmium Orange. It doesn't have the same high chroma, nor does it have the same opacity as cadmium orange. However, setting the cadmium discussion aside, in its own right this is possibly interesting pigment.

From a health and safety standpoint it may metabolize to a mutagen, and or cause methemoglobinemia according to Monona Rossol so please consult her work for more information.

It seems to have good lightfastness overall with a slight fall off in tints- we wish it were even a little more lightfast as it's a nice, not-quite-highest-chroma orange. Even though Gamblin describes this color as the same masstone as Cadmium Orange, we'd disagree based on their version of it, which does not share the same high chroma as PO20. We'd say this color is slightly less chromatic than cadmium orange.

PO64 - Benzimidazolone Orange (one of several). A rarely found artist pigment, used by one paintmaker in oils. Moderate lightfastness.

PO65 - Benzimidazolone Orange (one of many kinds). This one is fairly rare in artist paints. It's Used by Old Holland in Golden Barok Red. It has decent lightfastness.

Schmincke Norma Orange

High power oranges

PO67 - Pyrazoloquinazolone Orange. This is a nice red-orange that tints well, meaning it retains high chroma in tints. It does not turn as pink in tints as PO73 does, which is a slightly redder pink. PO67 doesn't seem to move Munsell hue much in tints, and is a bit oranger/yellower overall than PO73 with a bit less chroma as well and a bit more opacity. Even so, it has a bold bright middle orange in masstone. It is not officially rated by the older ASTM standard, however it does appear to be somewhere around an ASTM II in watercolor. In oil a couple of paintmakers give it high marks, so it may be worth doing your own lightfastness tests using the mixing white of your choice.

PO71 - Pyrrole Orange. Sometimes known as Transparent Orange or Transparent Pyrrole Orange. It's a deep, bright red orange. Some sources list this as ASTM II, others as decent to excellent on the blue wool scale. This is one of several DPP pigments (see below). Much more commonly found in watercolor than oils, PO71 is offered by only one major oil and acrylic paintmaker, however about 8 paintmakers offer it watercolor.

PO72 - Hostaprint Orange H4GL 32. This is listed with a lightfastness of excellent. It is rare to find it in paints, and one watercolor maker has included it in their line. however artiscreation advises doing one's own tests depending on the binder to see how it performs.

PO73 - Pyrrol Orange. Also sometimes known as Irgazin® DPP Orange and sometimes maybe even Cosmoray Orange. This seems to be an important synthetic orange- a possible alternative to the redder forms of Cadmium Orange, but it is less opaque and is also unfortunately a bit more reactive than was once thought.

Aside from the reactivity, it creates gorgeous light orangy-pink tints-- this is a good color if tints of cadmium red are desired-- it does in practice what many hope for from a cadmium. In other words, it fulfills that hope that one has when adding white to a cadmium. Pyrrole Orange makes what may be the very best red-orange tints with a hint of a pink undertone.

In masstone it's a stunner and has blazing high chroma.

Most give this pigment high ratings for excellent lightfastness, however there were some strange curveballs found in oil paints. In the recent testing by Golden, PO73 seemed sensitive to mixing whites and binding oils, specifically Safflower Oil. This may be significant as several companies offer this pigment in a safflower oil blend. For more, consult Golden's recent research on lightfastness in oil paints.

PO86 - Bismuth Vanadate Orange. This is a newer pigment and is thought to be highly lightfast. It's offered by at least one watercolor maker at the time of this writing.

PO107 DPP - The term DPP may refer to one of several pigments. DPP lacks a pigment code but may be Cosmoray Orange (Irgazin DPP)- the name Cosmoray can sometimes be conflated with PO73, so you might need to disentangle the two. According to Artiscreation, It may also refer to PO107 or PO108 (experimental). Both are reported to have excellent lightfastness. At the time of writing, it's offered by at least one major watercolormaker.

Powerful (and reactive) Pyrrole Orange

Yellow Pigments

Sunshine, Daffodils, and Marigolds

Perhaps surprisingly this is also an area where colors abound, but suitable colors may be harder to find when one takes a closer look. The quest for opacity and lightfastness leads us always back to the cadmium yellows.

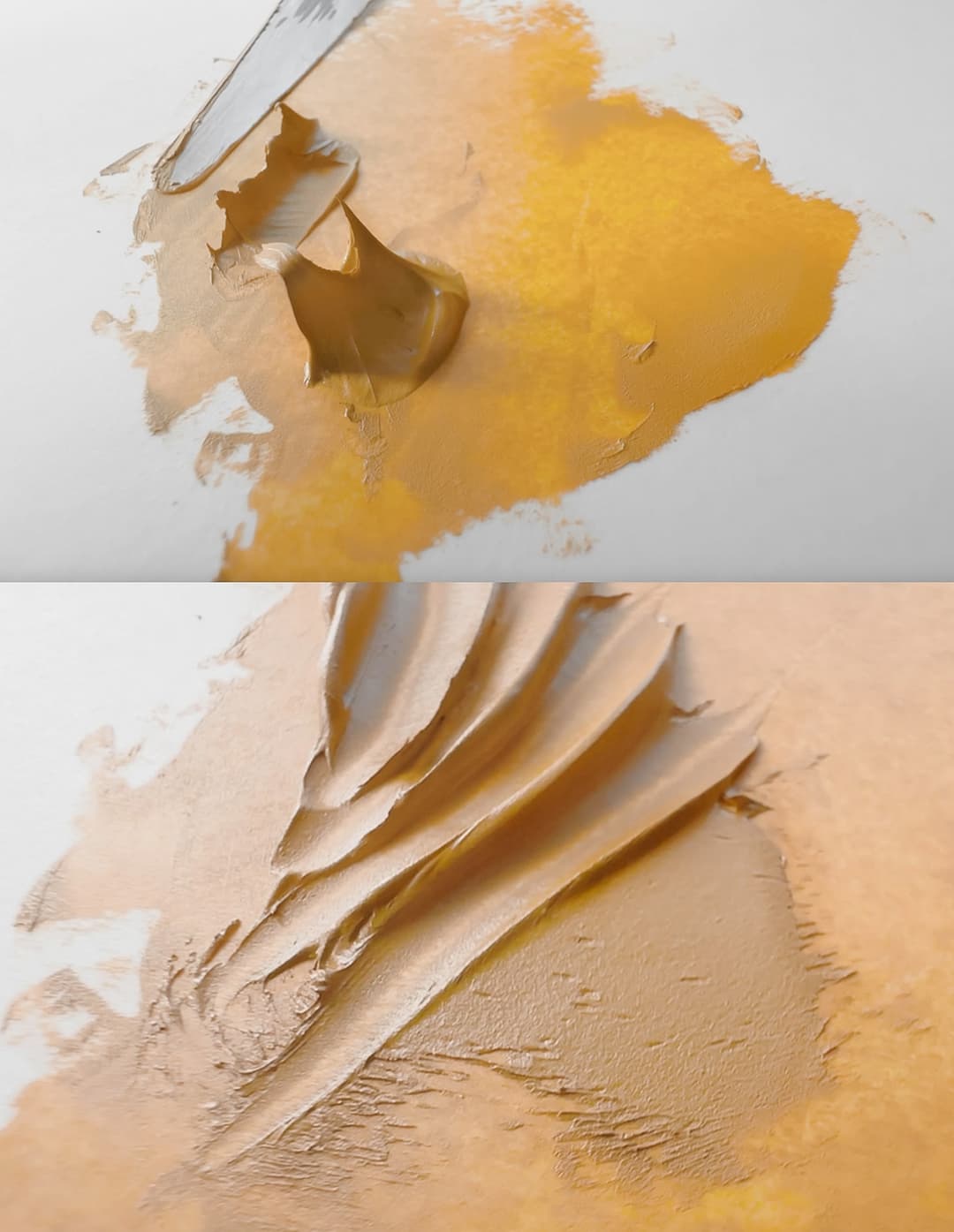

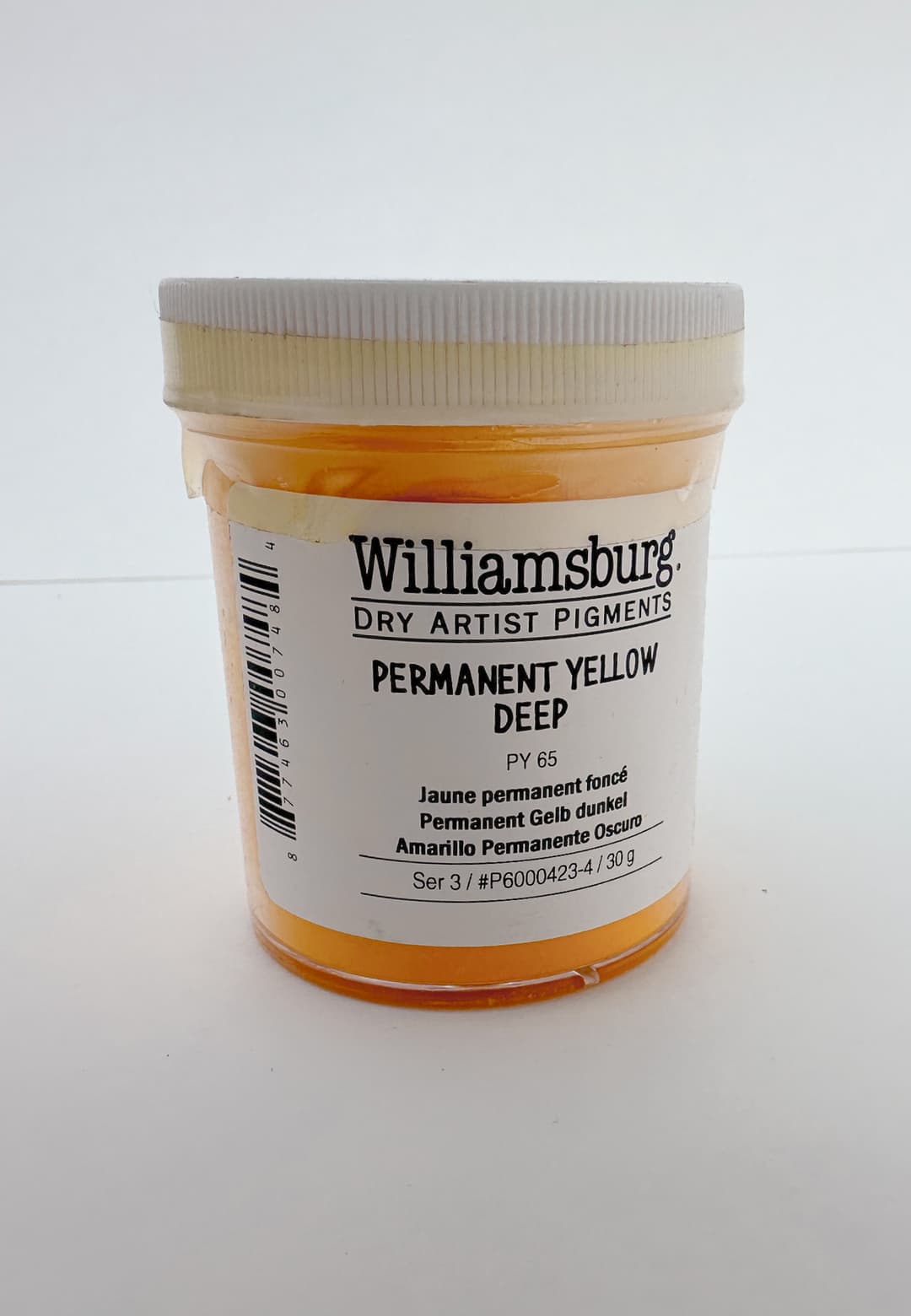

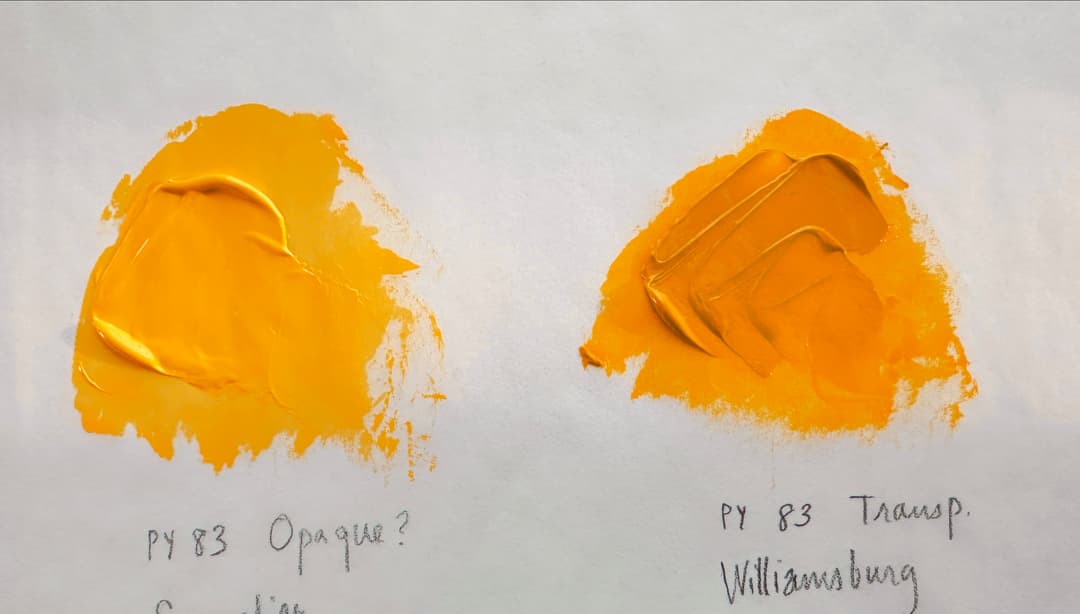

We've been grateful for Golden's work in sounding the lightfastness alarm regarding a couple of unexpected areas of the yellow gamut. Some of the Hansas started giving less than desirable lightfast readings, due possibly to differences in their pigment manufacture, and so Golden made changes to their lines. Golden also alerted the paint world to issues with some versions of PY83, particularly transparent ones.

Yellow pigments

Spotlight on Hansas

The Hansas are an area where you'll want to keep an eye on the lightfastness. They can vary from brand to brand. Also check out Golden's recent Lightfastness Testing. Oil painting occasions special challenges, so once again they rose to the occasion in their lightfastness testing with different mixing whites in oils.

PY1 - Hansa Yellow G. This has only moderate lightfastness, and sometimes the lightfastness can be very poor. Additionally it may release carcinogens, as well as cause methemoglobinemia, see Monona Rossol's work here for more information. Handprint recommends PY154 instead.

PY3 (Also known as PY3 10G).- Hansa Yellow 10G. We were surprised to hear that this is suspected to be a carcinogen. Additionally, it may possibly cause methemoglobinemia. Monona Rossol's research has more information.

Hansa Yellow's lightfastness is moderate in tints. This is one of the brightest Lemon Yellows. However there has been some variability in the lightfastness of Hansa Yellow pigments over the years, depending on the way they are manufactured, and its old assignment of ASTM II may not reflect the current pigment market. Artiscreation mentions "PY 97 or PY 154 are similar and more light fast, PY175 is a nice lemon yellow too." Tends to be a slow drier.

A bright hansa lemon yellow by Schmincke

Wild Yellows

PY14 - Diarylide Yellow AAOT, an Azo Yellow, Disazo Type 11 Toluidide. Lightfastness is reported by third party sources to be poor-- quite fugitive. This pigment may actually descend to a blue wool scale of 1 on a scale of 8, with 8 being good and 1 being basically falling off the bottom of the scale.

In addition to poor lightfastness this may metabolize to a known carcinogen, see Monona Rossol's work to learn more. She notes that it may also be contaminated with PCBs.

We were very surprised to find this pigment in artists oils. One manufacturer, who is quite well thought of, mentioned its stability and reports the lightfastness of their version as ASTM II, so perhaps there is some variety.

We wondered if there is some discrepancy somewhere, as artiscreation reports quite sorrowful lightfastness testing for PY14 with the low end of moderate for masstone and dramatic fading in tints. We wondered if there was a typo somewhere, and we checked the six digit code reported by the manufacturer (21095). It does indeed seem to be PY14 and both sources mention that the color is used mainly in printing. Perhaps doing one's own lightfastness tests would be useful.

PY17 - Dairylide Yellow 17. One company offers this as a single pigment paint and it also finds its way into a few blends. May metabolize to a carcinogen, and may also be contaminated by PCBs. See Monona Rossol's research for more information.

NY13 and NY14- Stil de Grain Genuine. This isn't a color name that gets used a lot, as the original is made from one of several sources. Historically there have been a handful of overlapping names surrounding the terms "Yellow Lake" and NY13 and NY14 are some of them. There a process involving quercitron bark (NY13), and unripe buckthorn berries (NY14), and both are fugitive. The name space still inspires paintmakers though. Dutch pink is another name that gets used, and sometimes causes a bit of confusion when painters find out it is yellow or brown. Artiscreation has an interesting discussion on NY13 and NY14 regarding the plants involved and the usage of the name Stil de Grain throughout history. We were amazed to find a recent Schminke version of this color available at Jackson's.

NY20 - Also known as Indian Yellow Genuine. It's sometimes debated whether this color actually exists, or at least if it was made in the way that is commonly told and re-told. A warm transparent yellow. The color at least does in fact seem to be real--regardless as to whether there was basis in the stories told of how it was manufactured. Golden has pictures of an actual sample of genuine Indian Yellow, or Magnesium salt of euxanthic acid. This is the infamous yellow that was allegedly made from cows made to eat mango leaves. A wide range of transparent yellows are available to artists, and so the name applies to a great many paints of other pigments.

NR24 - Genuine Gamboge. Traditional gamboge fades badly, and similar to Indian Yellow, the name Gamboge applies to a wide range of other yellow-orange pigments. Genuine gamboge is made of a resin from Garcinia trees. It is transparent. In addition to its lightfastness issues, Artiscreation mentions that it is poisonous.

Mussini just came out with two historical colors, one of which is Stil de grain, NY13. Available at Jackson's

Historical Yellows

PY31 - Barium Chromate, also known as Baryte yellow or in older literature as lemon yellow of even ultramarine yellow. This is a very rare color in oils, and is currently only produced by Michael Harding. Blockx used to manufacture this color, but the Blockx version has not been seen available in the United States for some time. It is an enchanting green-yellow. However this fascinating color is also toxic. It often has a greenish note to the pale yellow.

Its toxicity is listed as C class, meaning "Hazardous, use appropriate precautions for handling toxic substances, especially if working with the dry powder; Do not ingest; Avoid dust & spray." See the Artist's Guide to Health and Safety for information about the hazards of pigments containing Barium and also pigments containing Chrome.

PY32 - Strontium Chromate. This is likely extremely toxic.

A lively, hard-to-find bright yellow, which is prized by some painters. The quality may vary a lot depending on the pigment and the way the paint is formulated- we have two samples which have fared quite differently. One of the two was a very slow drier. It has a bright yellow character - the paint we have tried in oil is similar in hue to a cadmium yellow lemon. Artiscreation mentions that "may turn greenish due to the partial conversion to chromium oxide."

Artiscreation classifies it as a "B" for toxicity, however please always err on the side of great caution- we would also consider this pigment toxic though we are not toxicologists. See the Artist's Guide to Health and Safety for information about the hazards of pigments containing Strontium and also pigments containing Chrome. We have read this pigment is extremely toxic.

PY34 - Lead Chromate. A very toxic pigment that contains both lead and chromate. A carcinogen. Once when I met a chemist at an art demo and mentioned chrome yellow, his eyes widened and his eyebrows leapt up and he warned me of its extreme toxicity due to Chromium IV/ hexavalent chromium. Artiscreation lists the toxicity as "C", meaning "Hazardous, use appropriate precautions for handling toxic substances, especially if working with the dry powder; Do not ingest; Avoid dust & spray." See the Artist's Guide to Health and Safety for information about the hazards of pigments containing Lead and also pigments containing Chrome.

Besides this there are other reasons to wonder about this color as it is known to darken- though modern means of manufacture may help to mitigate this somewhat by coating the particle. Of the two modern paints we've tried they had masstones similar to colors in the cadmium yellows, though they did mix differently than cadmiums. Of the two we've tried, the primrose variety showed some color shift, possibly due to the sample we made having been later stored in the dark. We have heard of differences in manufacture that can mitigate darkening somewhat, however that goes beyond the scope of this article, and we feel the drawbacks outweigh any benefit. Please treat this pigment with extreme caution. Our experience with this pigment tends to be a slow drier, though we have read that it is a fast drier in other places, so it is not clear what gave rise to that difference.

We recently learned from an older manuscript that these toxic chrome yellows used to be used to adulterate more expensive cadmium yellows. So be aware that they may be hanging out undisclosed in old tubes of paint. They were also used to give a little boost to ochres, a trend that Rublev nods toward in their Chrome Ochre blend, which shows an awareness of this chrome-ochre convenience blend. We mention this as the health hazard of a chrome yellow may not have been disclosed on old tubes of yellow ochre, nor on old tubes of cadmium yellow. People may not realize how toxic these could be.

Vintage Strontium Yellow

Cadmium Yellows

Stars of the high chroma palette

Jim Harris (aka Gunzorro) once wrote of a "fairly stable rainbow." For our paintbox, this is one of our main top choices for the core notes of yellow.The opacity and high chroma are some of the reasons we adore cadmium yellow. It comes in Light, Medium, and Deep.

To get an idea of the color ranges for these names, we compared a few cadmium yellow lights in oils. Here are some comparisons of cadmium yellow deeps and mediums.

PY35 - Cadmium Zinc Sulphide. Glorious high chroma yellows ranging from bright citrusy lemons to middle yellows to warm marigolds. This pigment can almost dip to orange. Paintmakers offer them in Lemon, Light, Medium, Deep and Extra Deep. More information below.

Cadmium Yellows It can be helpful to have a wide range of cadmium colors as each one can provide a note of high chroma at a slightly different hue angle. This arpeggio of yellows provides a very good backbone for color mixing, and using a string of cadmium yellows one can easily find one's way around mixing greens, mixing oranges, and using the knowledge of these colors for any subject.

It is recommended by painters who favor the cadmiums to have a lot of different choices from a lot of different brands. The reason for this is not to benefit paintmakers, rather each paintmaker chooses the notes of color from a wide gradient of available choices from lemon yellow to marigold so the names Light, Medium, and Deep vary tremendously from brand to brand. Sometimes a Cadmium Yellow Medium in one brand will equate to a Cadmium Yellow Light in another. When starting out, a person can pick a Cadmium Yellow Light and a Cadmium Yellow Medium or Deep to simplify the options and learn color mixing.

We compare several Cadmium Yellow Lights in oils, as well as several Cadmium Yellow Deeps.

Something fascinating about cadmium yellows is the way the add lightness to a mix- especially Cadmium Yellow Lemon. For some applications a person wants transparency or does not want this lightening, so we would recommend other pigments for transparent yellows (see note on PY110, also PY150).